Who In the World Do You Think You Are? Week #4 of 52 Mini-Essays Project

On 1970s musicals and making friends

Topic Idea: Nora Gilbert, sort of (I promise to write something about Bob Fosse one day!)

If there is one thing I have come to understand during my time on earth, it’s that you are either a Sondheim person or a Rodgers and Hammerstein person.1 (Of course, there are a few nuts out there who profess to love both equally, bless their hearts. Let us not even speak of those who do not love musicals.) Your typical R&H fan still alive today probably came to love Oklahoma! and The Sound of Music as I did, by listening to their parents’ records, and undoubtedly suffers from ongoing low-grade trauma over the misogyny, heterosexism, and (probably?) racism2 of the duo’s toe-tapping, finger-snapping œuvre. Your typical Sondheim fan, on the other hand, likes to imagine they are edgy and avant-garde. (“It’s a musical ... about a murderer!”) I’m fairly sure it goes without saying, but I am a hopeless Rodgers and Hammerstein fangirl—simply out of happenstance. My parents’ record collection was stuffed with old Broadway cast albums from the 1940s and 50s, which I listened to on constant repeat on weekend afternoons while languishing at home being a weirdo with no friends, whereas I had never even heard of Sondheim until college. He simply passed me by.

When my friend Nora suggested I write an essay about the musicals of the 1970s—I know in her heart of hearts she was hoping to read something about Bob Fosse and I am sorry—at first I thought, “Welp, I can’t do that since I am so completely and utterly not a Sondheim person.” But then I thought of a loophole. The most glorious, the most confusing, the eeriest and most disturbingly tuneful loophole of all time: Jesus Christ Superstar. Before we go any further down this road together, let me hasten to say a couple of things: 1. I will try to make this reading experience entertaining even to those who do not know the show. I don’t know what the hell you’ve been doing with your life, but even the criminally insane deserve basic human consideration and the protection of the laws. 2. I hereby officially apologize for everything Andrew Lloyd Weber did after Superstar. I don’t know what happened. It’s one of the great mysteries—and tragedies—of our time.

I almost hesitate to write about Jesus Christ Superstar because I fear it will be like a Mormon describing their initiation ceremony: my feelings about that show are too private, too sacred, too sublime perhaps to be put into words. It doesn’t have anything to do with religion (at least not in any straightforward way); it has to do with friends. After spending my childhood mostly alone, reading Nancy Drews and listening to Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass and Nat King Cole and his Orchestra (I don’t think anyone had listened to my parents’ records in decades before I figured out how to lift the stacking arm on the turntable and load it up with LPs), I finally found my people in junior high: the theater nerds. My BFF throughout high school and college, Nancy, was (and still is!) an extraordinarily talented musician and composer with a beautiful singing voice. The sunken den of her family’s house was the most glamorous and exotic place I had ever seen—it had no furniture except a baby grand piano and huge piles of pillows—and it quickly became our gang’s hangout on weekend nights. We would gather there as often as our parents would permit and stay up till the wee hours, lounging on the pillows, eating snacks I wasn’t allowed at home, singing along to cast albums and Nancy’s accompaniment on the piano, and dreaming of our future on Broadway. We worked our way through the Great American Songbook and classic musical cast albums, but we also developed a private, quirky repertoire of more contemporary fare we would return to over and over again: Hair, Fame, A Chorus Line,3 Pink Floyd’s The Wall, Godspell, Harry Chapin’s Greatest Stories Live. We had these albums memorized. But towering above them all—the monolith, the eidolon, the beau ideal—was Jesus Christ Superstar.4

The plot of the show is probably familiar to most and can be dispatched fairly quickly—it tells the story of the last few days of Jesus’s life, cobbled together from the Gospels, various apocryphal sources, and vintage Bazooka gum wrappers. Judas does some bad stuff, the Jewish high priests do some bad stuff, the Romans do some bad stuff, the crowd does some bad stuff, and Jesus dies. (More on that last point later.) It’s the music that’s squarely at the heart of the Superstar experience, perhaps even more so than with a traditional musical.5 When you listen to JCS over and over, you begin to notice how beautifully the whole thing fits together: the way that motifs associated with each character thread their way through the bass or melody lines of songs in which they appear, the repetition of musical snippets as lead-ins or codas to other songs recalling plot points or themes from earlier in the show. I now realize, of course, that any musical worth its salt does this—one of the great joys of watching a sitcom with composer Jeff Richmond at the helm is getting all the little musical in-jokes with which he peppers his scores—but it was Jesus Christ Superstar (okay, and maybe a little bit of Peter and the Wolf) that taught me to recognize and appreciate this kind of subtle attention to detail.

Then there was the sheer titillation of the musical itself. Jesus and his apostles were depicted as a bunch of low-key dudes you could imagine chilling out with around the cistern, and there were tons of contemporary references—Judas being harassed by reporters, Jesus overturning tourist postcard kiosks and tables full of aviator sunglasses in the Temple-cleansing scene, and p.s. Pontius Pilate is totally gay. There was also the reverent irreverence of the up-to-date slang (my favorite was a disciple who utters “Hey cool it man” to Judas in a perfect Lebowski-avant-la-lettre drawl). To me and my Gen X friends, hippie fashions and argot were the epitome of cool. We idolized the Boomers who were our older siblings or young parents (my parents had children quite late and were stodgy Silent Generationists, to my endless embarrassment). From the perspective of the Reagan era, the 1960s seemed like the last great gasp of political energy, social and sexual experimentation, and general questioning of outworn mores—and we were devastated that we had missed it all. The best we could do was wallow in the warmed-over counterculture of Superstar, Hair, and Godspell and lament that the revolution was over.

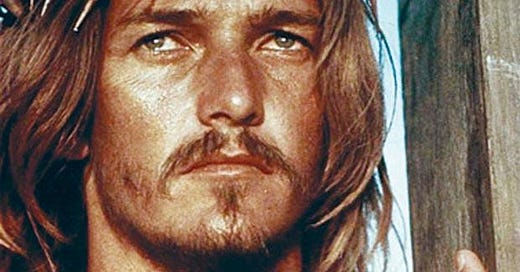

Finally, there was the risquéness of the religious stuff—all modern and realistic and provocatively up-to-date. Jesus is depicted as a brilliant prophet and preternaturally enlightened person, but the question of his divinity is sidestepped—the show ends with the crucifixion and death, full stop.6 You do not have to be Christian to appreciate Superstar; in fact, I suspect that it kind of helps if you’re not.7 (That said, at least one of my high school friends became briefly born-again under the influence of this album; I’m not sure he ever found a fundamentalist church that was cool with Jesus and Mary Magdalene being lovers and the disciples gallivanting around in midriff-baring crop tops.) The show managed to piss off absolutely everyone: Christians denounced the representation of Jesus as blasphemous; Jews denounced the depiction of the mob as anti-Semitic; atheists found it too religious; vendors of tourist postcards and aviator sunglasses felt personally attacked. But really the spiritual crux of Superstar turns out to be surprisingly anodyne: Jesus is depicted as a vaguely existentialist-Buddhist-maharishi type whose teachings do not depend one bit on his being the Messiah (or not). Its lightly angsty message is pitched perfectly at annoyingly “deep” teenagers the world over; I will never forget the visceral chill I used to feel when Ted Neeley sang-whispered the immortal line “To conquer death, you only have to die.... You only have ... to die.”

The real topic of Jesus Christ Superstar is not a lightly angsty spiritualism but rather a lightly angsty politics. The show’s lyricist, Tim Rice, described his portrayal of Jesus as being “simply the right man at the right time at the right place.” The show highlights the context of the Roman occupation of Palestine and depicts Jesus’s followers as seeking a political leader who will spearhead an uprising against Caesar’s army. (I am embarrassed to admit that to this day I have no idea if this reading is historically accurate or not, my knowledge of ancient history and my knowledge of the Bible being equally idiosyncratic.) The show is larded with “edgy” political references, and the 1973 film version even featured Judas—who betrays Jesus because he wants to keep the focus on worldly matters and ditch the god talk—being chased by Israeli tanks across the desert. (Topical! Then and now!) Perhaps by the early 70s the Boomers were also starting to feel that their revolution was getting a little shop-worn, and cultural products like Jesus Christ Superstar performed a largely compensatory function.

I’m going to go out on a limb here and point out that the story of the Passion, when stripped of any religious valence, is pretty dark. When the whole salvation of humankind thing is precipitated out, the moral of the story becomes: human relationships are expedient, coalitions are temporary, and your friends will ultimately betray you.8 It’s like catnip for an unhappy kid with a troubled home life who has only recently found her people: This whole friendship thing is cool and all, but I’m not going to count on it, or you.

And yet. Jesus Christ Superstar would find me again when I needed it most. Fast-forward a couple of decades to small-town North Carolina, where Scott and I had moved when he accepted a tenure-track job and I gave up a tenure-track job to follow him (we would perform this particular high-wire maneuver, in alternating configurations, a number of times). I was lonely and viscerally frightened that I had just lost my identity as an academic. The anxiety disorder I’ve struggled with my whole life came roaring back and I started having multiple panic attacks a day. Somewhere in that dark time I made a new BFF, a spunky historian of nineteenth-century France9 who had also just moved to town for a new job. God knows how long we had been friends—it was an implausibly long time—before we discovered our mutual obsession with Jesus Christ Superstar. One of the fondest memories of my life is the evening that Trish and I and our friend Andrea (with the same obsession! in the same small town!) banished our respective beaux to a bar,10 gathered in my living room,11 fired up a VHS tape of Superstar, and sang along to the whole show as we jumped up and down on the couches like lunatics. Fast-forward another decade-and-a-half after that, and the benevolent djinni of Jesus Christ Superstar would oversee me and Trish singing along at the top of our lungs with her two tween daughters, my spunky honorary nieces, as we watched the live Easter broadcast of the show starring John Legend as Jesus. (This sparked a months-long Superstar obsession in Mado and Juju, which I wish could have gone on forever but was eventually eclipsed by that upstart Jezebel, Hamilton.)

Would it be an exaggeration to say that this album saved my life? Only in the sense that unhappy kids with troubled home lives are saved by random emissaries from better and brighter worlds all the time: a sport, a hobby, the discovery of drag, a queer cousin, a visit to a museum, a ticket to the ballet. Finding my dorky (although—in precisely the way that Glee would teach us all decades later—also kind of cool!) people and bonding with them was the real point. Making a new friend in a lonely place was the real point. I’m still not 100% sure that I won’t be called upon to eschew worldly relationships and die alone for a greater spiritual purpose in the benefit of all humanity—I mean, how can you know? But in the meantime I think it’s probably okay to muddle along here on earth, doing some small works and helping others when possible and treasuring the occasional flash of insight and wisdom. We don’t have to be superheroes or gods. I think it’s okay to need your people.

A gross over-simplification, you protest! Well, of course. There is also the question of Rodgers and Hart, and obviously Lerner and Loewe. (R&H fans get to claim L&L as well. Sorry.) Plus Stephen Sondheim was mentored by Oscar Hammerstein II as a young man! If you are actually making these protests in your mind then you clearly already have your own thing going on, and we should agree to live together in harmony, mon semblable, mon frère. Hush now and go back to reading.

I had initially inserted that question mark as a placeholder to myself—investigate. Then I remembered South Pacific and (god help us) The King and I, and realized that investigation was not necessary.

Right this very minute “What I Did For Love” has popped into my head and I am so overwhelmed with nostalgia and sadness I can barely keep writing. How could this song possibly mean anything to a 16-year-old? And yet—it did. It did.

Again simply by happenstance—it’s what was floating around in Nancy’s living room—we became deeply attached to the movie soundtrack version with Ted Neeley as Jesus; to this day any other version sounds like a grotesque abomination to me. Not to mention the fact that the film soundtrack has an extra, wonderful song, “Then We Are Decided,” that features more of the ultra-creepy and fabulous voices of Caiphas and Annas—and also helps make the Jewish priests more sympathetic. Who would want to give that up?

I will not die on that hill, though—obviously I can sing every word of “On the Street Where You Live” on command but cannot reproduce a single line of dialogue that Henry Higgins utters to Eliza Doolittle, so I’m not sure how important dialogue/plot are to any musical.

The film does include a titillating new ending hinting more strongly at Jesus’s resurrection. The conceit of the film is that a bunch of cool hippie kids take a bus out into the Israeli desert to stage the story of Jesus’s final days; when they all pile onto the bus at the end, the actor playing Jesus is not with them. (Ooooo! Cue endless stoner speculation on the part of pile of teenage theater nerds.)

Of the four core members of our weekly sing-a-long group, I was the only one who was not raised Jewish.

I will also add that the stripping away of religious meaning leaves room for all kinds of confusing teenage feelings about sexy-beautiful Ted-Neeley-Jesus.

I am giggling uncontrollably as I picture her reading this phrase.

Me, to Scott, regarding this essay: “Are you sure it’s not boring if you don’t know the show?” Scott: “Not at all. And anyone who reads it won’t have to watch the show so you’ve performed a great service.”

Not sunken! No baby grand piano! And lots of regular furniture! But you can’t have everything.

Fascinating. JCS is so primal for me because my mother actually took 9-year-old me to see the original Broadway cast touring in Seattle in '72. She'd either just gotten the album, or did immediately after. She was a classical-music person with zero interest in rock, and also emphatically (?) ex-Catholic; we were probably equally out of place at that show & still can't understand why were were there. I mostly remember it as extremely loud with pyrotechnic lighting effects. But within a few months my brother and I had the album memorized, and could (and did) sing it end to end, frequently. We saw the movie when it came out the next year, and that was an intensely emotional experience. I was 10, he was 12. Musically, we were just getting into Elton John, and our standard filmic and tv narrative fare was all pretty light. I had nether musical nor narrative categories for understanding, contextualizing or really processing JCS; it was just an emotional storytelling firehouse.

At the time, my narrative identifications were probably a weird mix of Judas/Carl Anderson and Pilate/Barry Dennen. It took me literally decades to warm to Ted Nealey (remember that I'd gotten used to Ian Gillan in that role, and vocally there's really no contest); though more recently I appreciate Neeley's performance, esp opposite either Dennen or Anderson.

"You liar, you Judas...."

"Why don't I just stay here and ruin your ambition--Christ you deserve it!"

But Norman Jewison did have some fantastic movie ideas, as you mention. Temple scene, tanks, angel/jets. Also the montage of medieval iconography after "Just watch me die....see how, see how I die..." Still gets me.