Whence, Wherefore, Whither Utopia? Week #41 of 52 Mini-Essays Project

On everyday blueprints for the future

This essay originally appeared on 3 Quarks Daily.

What does the word “utopia” mean to the battle-scarred denizens of the twenty-first century? A shockingly unscientific survey of the nine or ten people I buttonholed last week suggests that the key connotations of the word are: ideal, perfect, imaginary, unrealistic, and unattainable. I’ve arranged these terms purposefully in that order, so that they imply not a static and fixed definition but rather a narrative arc, a falling away from hope into disappointment: all of the people I spoke to (students and colleagues at the large Southern state-flagship university where I teach, so a fair cross-section of ages, races, ethnicities, and genders) firmly believed that the word “utopia” denotes an unrealistic or quixotic goal. It’s not my thesis here that disappointment is the necessary fate of any utopian project, but it might be a provisional thesis that most people living in Western cultures today think that it is.

As a Victorian literature scholar, I’m a little surprised at how pejoratively the word “utopian” is used today. Because I immerse myself in another historical period for my research and teaching, I am forced to move back and forth, somewhat vertiginously, between the Olden Times I study and the present moment; just like H. G. Wells’s Time Traveller, I sometimes find it takes a few moments to blink away the “veil of confusion” occasioned by my most recent trip home from the nineteenth century. For the Victorians the word “utopian” did not carry the negative connotations of impossibility, naïveté, and dunderheadedness that it does for us now—the writers and thinkers who used that word were for the most part engaged in actual utopian projects, whether literal or literary (or both).1

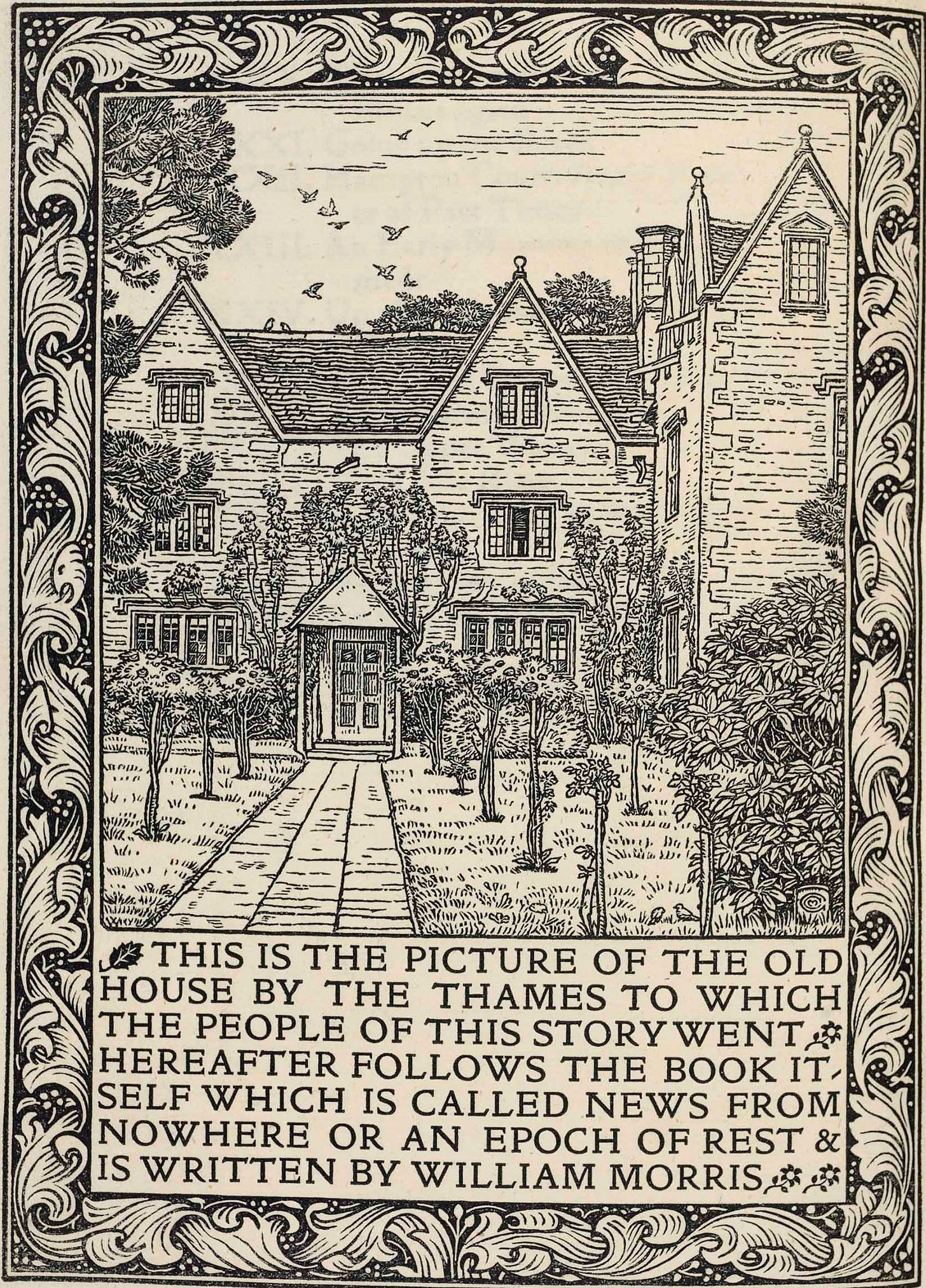

In addition to IRL intentional communities such as Oneida, Brook Farm, New Harmony, Fruitlands, and Clousden Hill, there was a remarkable efflorescence of utopian literature in the late Victorian period. The last couple decades of the nineteenth century saw the publication of over 400 utopian novels in English, fully half of which were published in just eight years, between 1887 (when Edward Bellamy’s hugely influential novel Looking Backward appeared) and 1895. Bellamy’s novel and William Morris’s response in News from Nowhere (1890) not only sparked a craze for utopia-writing that lasted over a decade; they jump-started a vogue for utopias set in the future. (The earliest examples of the genre, including Thomas More’s Utopia in 1516—which coined the term itself—tended to be set in isolated, “undiscovered” societies contemporaneous with the author’s own time.) Bellamy’s and Morris’s future-utopian novels form two ends of a spectrum: the former envisions an idyllic America in the year 2000 whose just and equitable society is enabled by technological development and the gradual consolidation of capital in huge monopolies eventually taken over by the state, while Morris sketches a future neo-feudal pastoral idyll in which human beings live in harmony with nature, dwell in small communal units, and labor by hand. Radically different pathways to the same basic place: a world of equality with no private property and governed by communities of care.

In addition to these two most famous2 late-Victorian utopias, there was the slew of other novels no one reads any more: W. H. Hudson’s A Crystal Age (1887), Walter Besant’s The Inner House (1888), Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of Tomorrow (1898), Anthony Trollope’s The Fixed Period (1882), and on and on. It’s my contention that these wacky, unappreciated novels still have something to teach us about how to think as utopians—that is, as people who believe that a much better (if not ideal) society is within theoretical reach. They invite us to reflect on both what we think can be achieved in social organization as well as the deep unspoken things we think are impossible—the unchangeable phenomena we ascribe to “human nature,” or just “nature.” Reading the utopias of an earlier time period can throw our own predispositions, predilections, and prejudices into sharp relief.

I’ve taught several courses on utopian fiction in the past few years, at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. Every one of those classes, when confronted with this new-to-them genre of fiction, has developed their own communal way of grappling with the strangeness of what they’re reading. One class started asking, of every new utopia they encountered, what the “Maguffin” was for that particular society: What is the barely spoken, offhand, and yet utterly crucial prop or feature without which the entire system would be impossible? (In News from Nowhere it would be river barges magically propelled by an as-yet-undiscovered green energy source, in Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s hollow-earth novel The Coming Race [1871], it’s “vril,” a kind of parapsychic fluid that renders the utopia’s denizens ultra-strong, telepathic, and impervious to pain.3) My grad class, on the other hand, started inquiring of each novel, “What does the author do about human nature?” by which they meant all the selfish and combative impulses that would presumably prevent us from living together in an egalitarian society for any length of time. (Getting them to unpack the idea of “human nature” was the work of an entire semester.) A closely related question was: What is the generational buy-in? How do these authors imagine a utopian society would get past the “hump” of its first group of inhabitants, who would have been socialized in another political structure? How do they envision creating better utopianists in the future?4

My very youngest undergraduates—at least as of a few years ago—seem already inured to the idea of their bankrupt future. I began teaching climate change literature in a freshman class in 2015, and the first couple of times I taught this material I was nervous about depressing the hell out of my students. I walked into the classroom the morning after I’d assigned Roy Scranton’s Learning to Die in the Anthropocene almost apologetic, expecting that we’d basically have to have a group therapy session. They shrugged when I asked them if they had been traumatized by the book. “No,” one of them finally replied to my prompting, “we’ve grown up with this stuff.” I’m still grappling with what it meant that these first-year students (who are now in their mid-20s) did not find climate change fiction particularly depressing—or rather, particularly surprising or disorienting. As I’ve written about elsewhere, I think our greatest hurdles in trying to think like utopians will be intergenerational.

So when, why, and how did we turn our backs on utopia? Or have we?

As long ago as 2008—years before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the assault on the U.S. Capitol, the Covid-19 pandemic, the election of Donald Trump, or the terrifying IPCC climate report in 2018—Thomas Homer-Dixon argued, in The Upside of Down: Catastrophe, Creativity, and the Renewal of Civilization, that it was high time to start imagining hopeful alternatives to Mad Max or Cormac McCarthy’s The Road for our inevitable post-apocalyptic future. A couple of years later, Rebecca Solnit’s Paradise Built in Hell was making a similar case but for the past rather than the future: her thesis (greatly simplified here) is that in the aftermath of enormous catastrophe—such as the San Francisco fire or Hurricane Katrina—human beings tend to band together in loosely improvisational communities of mutual aid rather than immediately start boiling one another for dinner in cast-iron pots. This utopian trend continues up to the present moment: hot off the presses are books like Joanna Macy and Chris Johnstone’s Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We’re In with Unexpected Resilience and Creative Power and Half-Earth Socialism: A Plan to Save the Future from Extinction, Climate Change, and Pandemics by Troy Vettese and Drew Pendergrass, an unabashedly utopian(ist) treatise that draws on William Morris and other Victorian thinkers in laying out its blueprint for a better future.5

And there are a smattering of more recent utopian novels, too. While the Victorians went mad for the genre, and it famously petered out after H. G. Wells wrote a couple of novels at the turn of the century that (not to put too fine a point on it) threw utopia under the bus,6 a few intrepid visionaries have continued to keep the idea alive in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries through fictional representations of ideal societies: Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Dispossessed (1974), Ernest Callenbach’s Ecotopia (1975), Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time (1976), and Kim Stanley Robinson’s Pacific Edge (1990), Mars Trilogy (1992-96), and The Ministry for the Future (2020) are notable examples. Most of these novels are science fiction, set on planets other than our own, which is a fairly depressing commentary on the state of utopian thinking regarding our actual, real, near-term future right here where we are.7

A few weeks ago I had the enormous privilege of gathering with a group of nineteenth-century humanities scholars working on environmental topics—not just colleagues, but friends—for our first working group/conference since the pandemic. This year, instead of a formal conference at a university, we decided to gather at the Wisconsin lake house of one of our members. We sat around the living room with windows open to the cross breezes from Lake Michigan and the sound of waves lapping on the beach as we discussed one another’s papers and book proposals: on oil culture and Moby Dick; silver mining in Conrad’s Nostromo; the literary history (and actual future) of wilderness; horticultural practices in the British Empire; the challenges of representing the vastness of ecological time scales in the Victorian novel.

We mostly hadn’t seen one another for a few years, and we were giddily happy to be in one another’s company again. There were bonfires on the beach, punch bowls of mai tais, giant communal meals, late-night and early-morning dips in the lake, and way too much staying up into the wee (and eventually less wee) hours of the morning, gabbing. There was lots of catch-up and gossip and bullshitting, but also lots of real intellectual talk about our work, the state of the world, what we were doing with our lives and why, visions for the future and what we hoped and feared would happen with our shared planet. (The best kind of talk jumbles all these categories together, when you start losing the difference between intellectual work and real life, when you remember for a minute that there shouldn’t be a difference to begin with.) There were far too many people in the kitchen at any given moment. There were bare feet.

Of course this is just my experience of the weekend, and you have to take what I say with a whole box of salt because this kind of experience is tailor-made to set off every dopamine receptor in my sociable little brain. I adore big gatherings, and I particularly love situations in which a bunch of people I love are trapped together and can’t leave me while I ply them with delicious food and force them to disclose their most intimate secrets—kind of like the Donner Party, but with better catering. And I don’t think I’m alone: the weekend house party is a time-honored setting for the nineteenth-century novel, and it’s the main reason that The Big Chill continues to charm viewers long after the navel-gazing angst of Baby Boomers has lost its cultural cachet. Who doesn’t like being jammed into a kitchen with a bunch of friends, loading the dishwasher while dancing to some great R&B?8

At one point late into our last evening at the lake, I found myself outside at a picnic table with T., talking about utopia. It was a crystal-clear night and the light of two full moons—one in the sky and one in the lake—shone on the narrow sandy beach and the grassy yard. I had presented a proposal earlier in the weekend for a book about ecological grief and utopias, both Victorian and present-day: I wanted to write something for thoughtful non-academic readers that might function as a kind of companion to the literary past and blueprint for a real-life future. T. wasn’t buying it. My proposal hadn’t done a very good job of explaining the type of utopia I was imagining or when it would come about: small-scale communal living, styled after the vision of William Morris, after industrial capitalism had been swept away either through choice or calamity. We kept quasi-arguing over the parameters of utopia, talking about the work of Kim Stanley Robinson in particular (with whom T. is actually friends—he refers to him as “Stan”9), when eventually it became clear that we were talking about two different things. T. thought that “utopia” implied large-scale centralized state planning, which is of course the exact opposite of what I meant to convey. Finally we understood each other, and after we’d sat for a moment in silence, T. turned to me and said, “So in a way this, here, now—this weekend. What we’re doing. That’s utopia.” I didn’t disagree.

In Morris’s vision in News from Nowhere, the lake house we were staying in would be owned by no one, and individuals and groups would move freely about the countryside, living wherever and with whomever they pleased as they followed seasonal work opportunities or just got bored and decided to move on. There would be no private property, no salaries, no money, and people would labor because of the sheer pleasure they took in the work. Of course this is an idealistic vision—a utopia!—and Morris spends huge chunks of the novel explaining how this new social organization comes about and finessing some of the more troubling aspects of “human nature.” But it’s not utterly impossible to imagine.

Right now our imaginations are crammed with collapsing glaciers, world-wide drought and famine, fascist dictatorships, nuclear war, and never-ending pandemics. I’m not saying we shouldn’t be worrying about those things, but in order to survive as a species (if that is what we decide we want—we may end up turning the keys over to the cockroaches), we need at the very least to have some ideas about what we want on the other side. We need intentional communities, small-scale agricultural communes, weekend house parties with friends, mutual aid, networks of local activists who spring into action to help in a disaster,10 community food banks, bars that become central gathering places after hurricanes.11 These are all models of living together that help us build up muscles we may need in a long and uncertain future. These are all utopias. Long may they prosper.

The Victorians also wrote dystopias, too, and the situation is a bit more complex than I have space to lay out here (for example, the word “utopian” was not a compliment for that eminent Victorian Karl Marx), but my main point is that the Victorians wrote a heck of a lot more utopias than dystopias, and a heck of a lot more than we do today.

Ha ha, I mean “English Professor Famous,” which is similar to “English Professor Funny”—like those knee-slappers in Shakespeare that your professor kept insisting you should find hilarious.

This is what I like to call the “Matrix Fudge.” As Morpheus explains to Neo, the AI machines running the matrix have enslaved human beings and are using them as energy sources because “the human body generates more bioelectricity than a 120-volt battery,” which “combined with a form of fusion” (MAGUFFIN ALERT) provides the machines “all the energy they would ever need.” That’s like declaring that a single peanut M&M, combined with 2500 other calories, provides all the energy the human body needs to function throughout the day.

One possible answer to the “human nature” conundrum is B. F. Skinner’s behaviorist utopia/dystopia Walden Two (1948), which describes a society in which all members are subject to operant conditioning from birth in order to produce “ideal” behavior. Unfortunately I had to cut the novel from the syllabus at the last minute because of time constraints, so I had to keep simply describing the premise to my students all semester long.

The line between utopianist future-building manuals and books purporting to help the reader deal with climate grief is blurry. Recent books that lean more toward the latter include Sarah Jaquette Ray’s A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety: How to Keep Your Cool on a Warming Planet, Joshua Trey Barnett’s Mourning in the Anthropocene: Ecological Grief and Earthly Coexistence, and Britt Wray’s Generation Dread: Finding Purpose in an Age of Climate Crisis. This is just a small sampling of recent offerings.

When the Sleeper Wakes (1899) and A Modern Utopia (1905).

But I have to give a special nod here to Robinson’s œuvre, which includes novels that imagine in gloriously wonky technocratic detail utopian societies that could exist here on Earth, given current real conditions.

It was at just such a gathering, a Thanksgiving weekend house party in Maine, that Mr. Waffle and I first met. (And a special shout-out to Riff, who insisted on putting on The Big Chill soundtrack as we cleaned up the kitchen in Wisconsin and made me think of the connection.)

Not only that, but T. and another member of our group, J., who had co-edited a volume together, appear as minor characters in The Ministry for the Future. If you happen to be reading this, Stan—or any other speculative novelists out there—I would very much appreciate being made into a minor character in a utopian novel. Thank you.

Shout-out to the Wise Women listserv in Oxford, Mississippi.

Shout-out to Lucky’s friend’s bar in Ocean Springs, Mississippi.

Your post was sent to me three times this week! As I’m currently writing a utopian novel and a collection of essays imagining a more beautiful future, I am so excited to follow your work here and to read your book when it’s done. Your article has already given me a lot to think about (and a giant reading list!) Thank you, and so nice to meet you!