Chances are you have strong feelings about karaoke. Whether you would rather be slowly roasted alive on a spit than sing in front of a bunch of strangers, or your friends have trouble prying the mic from your hands as you belt out patter songs from third-rate Broadway musicals at the local motorcycle bar, my guess is that mention of the word “karaoke” invokes some kind of intense response. Like Donald Trump, frozé, and corduroy vests, it’s a topic on which it is difficult to remain neutral.1 It’s also one of the few obsessions about which it has—incredibly—never occurred to me to write an essay. Given that approximately 87% of my cerebral cortex is taken up with deciding upon, practicing, and performing karaoke songs, and furthermore it is a topic on which I have inordinately strong opinions, this omission has been a real shocker. Props to Mr. Waffle for coming up with the fabulous title for this essay and prodding me to finally get ’er done.

Let’s get some definitional housekeeping out of the way first. What karaoke is (according to Dr. Waffle): amplified2 public3 singing4 over a back-up track from which the original vocals have been removed.5 (Apparently the original term is an amalgam of the Japanese words for “empty” and “orchestra,” which is delightfully lyrical and evocative.) You can perform karaoke in a public bar in front of strangers, in a private commercial karaoke room with just your friends, or in your own or someone else’s living room with a home system. What karaoke is not: singing in the shower, belting out show tunes around the piano6 (or James Taylor songs around the campfire), humming along to the music in your car. The singing needs to be amplified, it needs to be in some sort of public, and you need to be unaccompanied by the original vocal track. Yes, of course you can perform karaoke simultaneously with other people. The drunken karaoke duet is a timeworn rom-com plot device,7 and one of my fondest memories is performing “Hotel California” with two other middle-aged lady friends in front of a bunch of tipsy Gen Zers at a karaoke bar in Philly. (They ate it up.)

But the definitional technicalities only scratch the surface. We still need to consider the much more important, much more complex question of the spirit of karaoke. This spirit encompasses a vast penumbra of related topics, including etiquette, ethics, alcohol, performance, anxiety, and performance anxiety. Yet the guiding principle that subtends and governs them all, the solid core of the discipline, can be summed up fairly pithily: You must not care.

You must not care how you sound, or how your friends sound in comparison to you, or how other people judge you, or whether you get to sing the songs you want. I suppose if you want to get really technical about it, the Guiding Law of Karaoke is “You must not appear to care.” But given that the easiest way to appear not to care is actually not to care—and in fact, appearing not to care when you do care is a feat that has been pulled off only three or four times in the course of human history,8 usually involving psychopathy—we’re going to focus here on the practice of not caring for realsies. Because I might as well admit right now that my ultimate goal is to turn you, Dear Reader—and, frankly, every human (and some non-human9) inhabitants of planet Earth—into a karaoke person. My motives are entirely and cheerfully selfish: I want there to be more people doing karaoke so that there are more karaoke bars, more karaoke gatherings, and more friends with whom to do karaoke, so that I get to do more karaoke. The best way to accomplish this goal is to make karaoke less stressful for all.

Let’s start with an example. For one of my milestone birthdays, my beloved life partner arranged a karaoke surprise party.10 Not only that, but he did it in our own house: he bought me a home karaoke machine, set it up while I was diverted by a co-conspiritor, gathered everyone in our living room, and then presented me not only with the new toy but also with a bunch of friends ready to sing. As utterly delightful as this gift was on every possible level, the highlight of the evening—nay, perhaps of my entire life—was the indescribably horrible singing of our friend Camille.11 She and her husband Mike had chosen to sing a duet of “You Don’t Bring Me Flowers,” a moderately challenging mid-range sap-fest by Neil Diamond and Barbra Streisand emanating from the depths of the 1970s. (I have no memory of the cover of the album whence this single effloresced, but I would bet my house that it’s a soft-focus photograph with some kind of wavy-script font. In white.)

The performance began innocently enough. We were about halfway through the evening, and almost everyone had sung at least a couple of songs and had a glass or two of champagne. We were in the tenderloin of the party. Mike and Camille hadn’t sung anything yet, but I didn’t think anything of that at the time—lots of folks who don’t do karaoke regularly take a while to get warmed up, and they were clearly enjoying themselves. Then Mike announced that the two of them were going to do a duet, and asked Mr. Waffle to cue up the song. A ripple of excitement ran through the room: it was our first duet of the evening and the first song from these two friends—and it was Barbra and Neil! I settled into my seat in pleasurable anticipation and took another sip of champagne as the tinny music swelled from the metal grille of the karaoke machine. The first verse is Neil’s, and Mike did a thoroughly respectable interpretation, hitting all the notes and introducing some modest song stylings of his own. There was a brief musical interlude before Barbra’s part came around, and Camille lifted the microphone to her lips and began to sing.

I feel it’s important to note here that Camille is a very dignified person: a brilliant scientific researcher in charge of millions of dollars of grants, with a Ph.D. and her own lab and a bunch of grad students doing what she tells them to do just for the opportunity to learn from her. She is diminutive but fierce, with a charming Belgian accent, and does not suffer fools lightly. Another significant datum I feel compelled to share is that she had not had a single drop of alcohol all evening: she was the designated driver, and adhered to her role with monk-like dedication. What happened next happened under the influence of no mind-altering substances whatsoever, unless you count a birthday cake sugar high.

The sound that emanated from the elegantly dressed, well-shod, perfectly coiffed frame of my friend Camille defies description. I would not call it singing, exactly; it was more like an enthusiastic, full-throated shouting only tangentially connected to the music emanating from the speaker. Its most salient feature was its utter lack of pitch. I had heard the phrase “tone deaf” before, but didn’t think I had ever met someone who truly could not tell if one note was higher or lower than the other—and yet here was a pure example of the type, a rare (non-) musical unicorn in our midst. Camille’s voice swooped up and down and around the musical scale with no regard whatsoever for the placement of notes in the original song. It was breathtaking.

We all sat in stunned silence for a few moments as she cheerfully forged her way through the first few lines of her part. And then everyone burst out laughing—we couldn’t help it. I personally thought that perhaps she was joking—giving us a parodic version of a “Bad Karaoke Performance,” à la Cameron Diaz in My Best Friend’s Wedding. It quickly became apparent that she wasn’t joking, but by then it was too late. We were all howling with laughter, doubled over, unable to breathe. And we couldn’t stop. Camille kept on singing, and we all kept on laughing. It was perhaps the hardest I’ve ever laughed as an adult;12 at one point I thought I might actually throw up. The fact that she was laughing along with us—she knew she was terrible, and was enjoying our enjoyment of her insane performance—only kept the hysteria going longer. (We’re not sociopaths, after all.)

And yet—and yet. She sang with brio, with verve, and without the slightest trace of shyness whatsoever. Her performance of the song—aside from the pesky matter of the singing—was an utter delight. Her voice was full of emotion and intensity as she looked tenderly at her husband and wailed “Baby, I remember / All the things you taught me.” She made eye contact with her listeners, touched Mike gracefully on the arm, stood up at the climax of the song and basically belted the hell out of the thing. Her godawful singing was in hilarious but poignant contrast to the bleak lyrics and stirring grace of her performance. Our laughter was drowned out only by our enthusiastic applause when they were finished.

The reason Camille’s rendition of “You Don’t Bring Me Flowers” will be forever enshrined in my personal Karaoke Hall of Fame is not, obviously, because of her brilliant vocal stylings. It’s because of the generosity of her performance and her adorable earnestness. It may seem as though I am now contradicting the Karaoke Prime Directive to not care. It’s true that Camille poured her heart and soul into the duet, but she didn’t care how she sounded or looked or was judged. This is a subtle but important point, and it’s worth emending the rule with which we began: You must be in earnest, but you must not care.

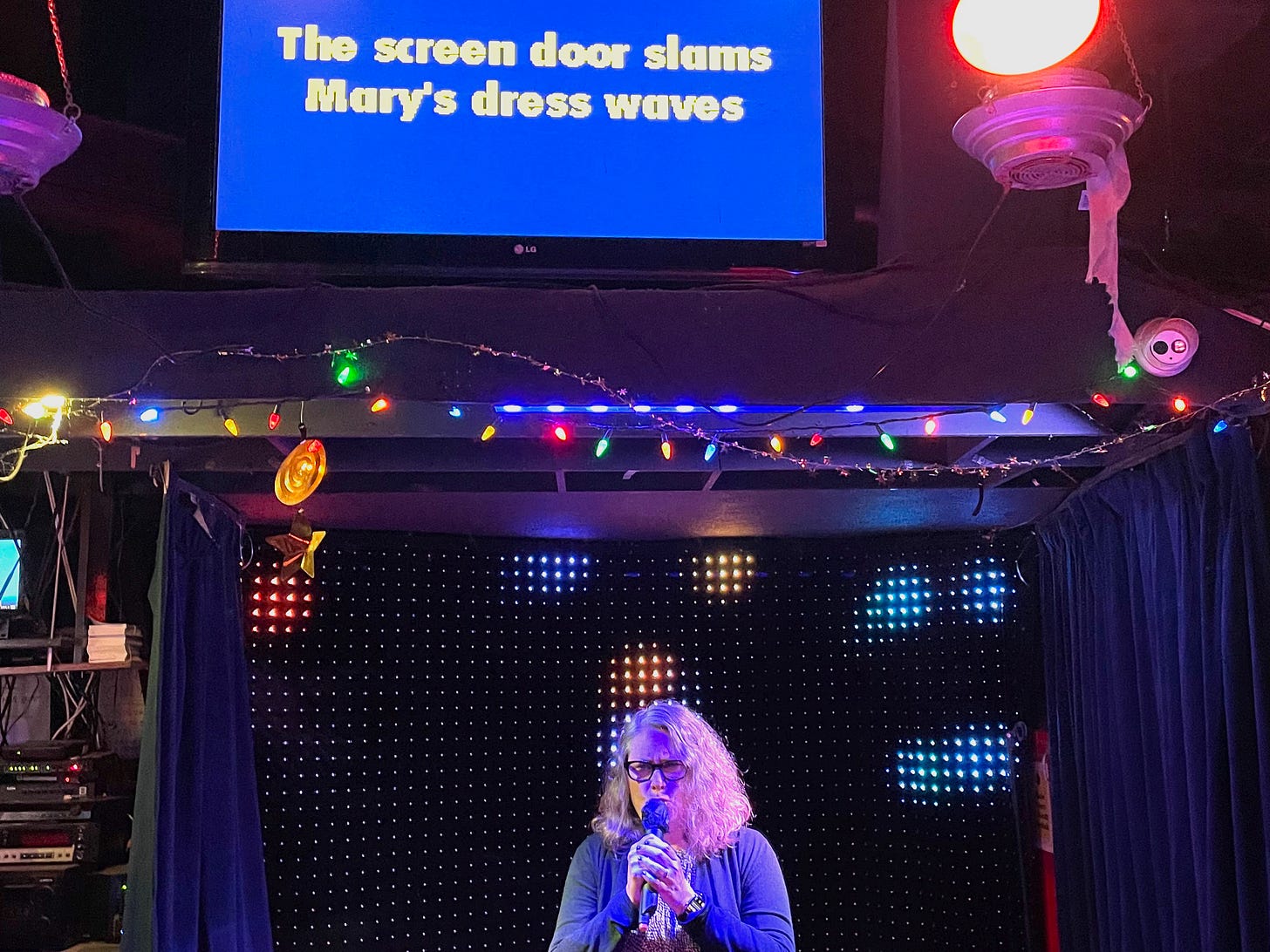

Another example will help illustrate this seeming paradox. A couple of years ago I was at an academic conference in Seattle, and a bunch of my fellow conferees and I decided to visit a venerable local tiki/karaoke bar at the end of a long day of delivering papers about environmental themes in Shelley’s poetry and whatnot.13 We got there early, so folks in our group managed to get a couple of songs on the list before the bar was over-run with local hipsters. (I believe I performed my old standby, “Thunder Road,” to the usual lukewarm acclaim.) About an hour or so into the evening, it gradually became clear to us not only that none of our songs was being called by the karaoke jockey (or “K-J”)—it’s normal in a crowded urban karaoke bar to get to perform only one song in an evening—but also that all the performances we were seeing came from the same table of about 8 friends. And they were good. Like, really good. Disturbingly good. These chowderheads not only had gorgeous Broadway-worthy voices; they also had enormous stage presence and interacted with the audience like pros: eye contact, smiling, adorable pointing, advanced microphone stylings. The star of the evening was a woman who stood up and did a barn-burning performance of “The Chain”—including the secondary vocals!14—that was literally better than Fleetwood Mac. My friend Cristie and I agreed afterwards that we felt like we’d been at a concert.

But. It was not exactly fun. Yes, the performances were highly enjoyable, but the whole thing felt like a bait-and-switch. (We later learned that the table of songsters were musical theater students at a local performing arts college.) We came prepared for a participatory evening of making thorough fools of ourselves, not a sit-back-and-watch-how-it’s-done experience. The young singers hogged all the slots, aimed their performances only at one another, and talked and texted throughout the (rare) songs by people not in their circle. But what ultimately left me and my friends feeling hollow, even in the midst of our appreciation, was the stink of caring that came off the young performers. They were earnest, yes, but they also were clearly in it for applause and admiration. They were ultimately sealed off from their audience—pointing and smiling notwithstanding—in a masturbatory bubble of self-regard. There was no room for real connection.

Using these two examples—my friend Camille and the local Fame kids—we can imagine a Venn diagram, or better yet a chart, delineating the True Spirit of Karaoke:

Notice what terms are missing from the chart: Good and Not Good. It doesn’t matter that Camille’s singing was bad or that the ringers at my conference were good—she still embodied the spirit of karaoke while they did not. Conversely, one can absolutely be a good singer and still perform in the right spirit (many of my friends fall into this category!), just as one can be bad and still not get it at all. Earnestness without caring: that is the key.

If this essay were a speech in a movie—say, The Karate Kid XVIII—at this point my interlocutor would open wide his youthful eyes and nod sagely as it began to dawn on him that I am not just talking about karaoke here. As in karaoke, so too in life: the paradox is that in order not to care, you have to give it your all, and vice-versa. If you care too much about the outcome, you will be self-conscious and tentative—in karaoke, in tennis, in courtship, in pizza-making. Only by not caring are you free to throw your whole heart and soul into an endeavor—in short, to be earnest.

Another possible thing my Karate Kid listener might be thinking is: Who made you the boss of me? I will think about and perform karaoke however the hell I want, Dr. Bossy Boots! And my reply would be: Fair enough! And then I would add, sagely: Well done, grasshopper. For in replying thus, you have demonstrated that perfect balance between Earnestness and Not Caring for which I have encouraged you to strive. There is a story (probably apocryphal, but who cares?) about Samuel Beckett learning that theater-goers had walked out of the first staging of Waiting for Godot and then replying “Good! They understood it.” If you have your own special relationship to karaoke that contradicts everything I’ve said here, I say go for it and god bless. Anything that keeps you coming back to the mic, the tinny music, the garish lights, the watered-down drinks, and your sweaty laughing high-fiving out-of-tune euphoric friends.

You will be getting an invitation to my next karaoke bash very soon.

But seriously? The people who are “undecided” about whether or not to vote for a convicted sex offender who tried to overthrow the U.S. government? I would not want to sing with these people in a public place.

Yes, you need a microphone and some kind of sound system. Amplification makes everyone sound better.

Technically, I suppose, amplified singing done completely alone in the privacy of your house is still karaoke. But come on.

The hardest term of all to define! Of course you may speak your song like Rex Harrison, or rap, or hum, or whistle, or mumble, or hit not a single correct note. These all count as karaoke for the purposes of this essay.

Some karaoke systems and mixes retain the original vocals—lead and/or backup—at a reduced, occasionally adjustable, volume. This prop can help a lot with a new or difficult song. That said, these are training wheels and should be abandoned at the earliest possible opportunity.

This is a wholly different and most excellent activity, properly the subject of its own essay.

Of course this exists.

Years ago I read an Ernie Pook’s Comeek strip in the Chicago Reader that I’ve been trying to find ever since. The gist is that teenage protagonist Maybonne has developed a crush on a boy at summer camp. They spend a lot of time holding hands. Then one day he turns cool, and she figures it’s because she’s not playing hard to get. So she tries to act as though she doesn’t care any more, and is all fake-nonchalant about the hand-holding. But the boy can just tell—her caring vibrates through her fingers where he can easily pick up on it. At the end of the strip she addresses the reader directly, saying something like, “You can’t fool someone into thinking you don’t care. Good luck faking it.” Good luck faking it.

My cat Jiffy Pop, who is intensely sociable and loves all other parties, abhors karaoke. Actually, she abhors singing—she thinks when people sing they’re shouting, and she thinks that shouting is fighting. Lest you accuse me of anthropomorphizing my cat: the second that Mr. Waffle and I raise our voices at each other, JP starts meowling piteously and leaping—leaping—many feet in the air and hurling herself against our bodies, sometimes as high as our shoulders, to try to get us to stop. She does the same thing as soon as someone begins to sing. Many a brilliant home karaoke performance has been (hilariously) interrupted by JP throwing herself bodily against the singer, shoving her head between mouth and microphone in order to ascertain that her friend is not dying.

I am devastated that Mr. Waffle made me remove the sound from this video

Another topic about which it is impossible not to have strong feelings. Perhaps unsurprisingly, I adore them—both giving and receiving.

Names changed to protect the innocent.

The other possible candidate is this scene from the 2009 movie Adventureland. I saw it in the theater with Mr. Waffle, and we were laughing and gasping for air so hard we had to step out of the theater.

This formulation makes it sound like a rare occurrence, but I pretty much always do karaoke at academic conferences. The eighteenth-century literature scholars will try to tell you that they started it, but we all know that the Victorianists are the most fun.

“I can still hear you saying / We would never break the chain (never break the chain)” as well as “And if you don't love me now (you don't love me now).” This is really hard to pull off without sounding like an out-of-breath ventriloquist’s dummy.

I love this! I don't like doing public karaoke for exactly this reason. I had a karaoke party when I left Nashville and another for my 40th. I like karaoke in small, safe places w/friends. It is the best.