Ted Bundies I Have Known: Week #46 of 52 Mini-Essays Project

On serial killers, pop stars, and the people who love them

This essay originally appeared on 3 Quarks Daily

I really don’t understand those podcasts where young women with their whole lives ahead of them spend an hour each week obsessing over serial killers. There are between one and 87 of these shows—I don’t know their names, I’ve never listened to them, and frankly I don’t want to know more than I already do. I am resisting Googling. But I’m aware of their existence because middle-aged women with half their lives ahead of them keep urging me to listen. The last time this happened, I was at a dinner party where I was regaled with a description of a podcast’s description of the Golden State Killer (do not Google!) over pasta carbonara and a nice Soave Classico. I spent the next few months obsessively checking and re-checking the door and window locks every night, then huddling under the covers in fear as I waited for sleep. I’m pretty sure there’s still a knife under the mattress “just in case.”

To be clear: I understand the pleasure of these shows. In fact, I understand it all too well—which is why I have no desire to start listening. I too have found myself crawling out of a Wikipedia rabbit hole of an evening, blinking in confusion and wondering why I just spent two hours of my time on earth compulsively reading about the exploits of Robert Pickton (do not Google!). What I don’t understand is how people can wallow in gruesome descriptions of psychopathy, gleefully taking in all the grisly details of murders, rapes, cannibalism, and the rest of it, and then calmly go about their daily lives. I’m not sure if my problem is mild undiagnosed OCD or just a hyper-sensitive nervous system, but once I get those images in my head I cannot get them out. Even the movie Titanic was too much for me—I left the theater shaking and sick with crying, watching in amazement as people around me in the lobby chatted about where to go for dinner. Avoiding images and descriptions of murderous mayhem is a discipline I follow that allows me to continue functioning as a moderately productive member of society.

But I think there’s something else going on with these serial killers, at least for me. There is something paradoxical, a bit perverse, and perhaps even unhealthy in my repulsion-attraction to the Ted Bundies of the world—I guess that’s a fairly obvious thing to say, but bear with me here. For one thing, I struggle with where to put them in my grand moral scheme of the universe. As a rational, secular Buddhist-wannabe, I do not believe in good and evil—and yet. Aren’t some actions, and maybe even some people, kind of, well … diabolical?

Many years ago, when I was still in grad school, I had one of those trippy late-night conversations with a bunch of friends in which everyone gets super deep about the Big Questions of Life, and to my great shock one of our group, who was training to be a clinical psychologist, said that she did, in fact, believe in the existence of evil. When she was quite young, her older brother had been the victim of a serial killer. He was attacked (I am redacting the details here because—reasons) and left for dead by his assailant, but survived and was able to give evidence that later led to the killer’s arrest and conviction for a series of rapes and murders. She was deeply affected by these events (I mean, duh) and decided to pursue a career in clinical psychology so that she could better understand the mind of her brother’s attacker and others like him.

At the time we were having our late-night convo, S. had been doing clinical training in a maximum-security prison, where she counseled perpetrators of the most violent crimes. As a bunch of us sat around in a friend’s basement apartment, rapt, she related the story of her brother’s attack and her subsequent decision to devote her life to working with hardened murderers.

“So yeah,” she said solemnly at the end of her narrative, after taking a contemplative sip of warm beer. “I definitely feel, when I’m in the presence of these men, that there’s something profoundly wrong with them—they’re almost non-human. I don’t know what else to call that other than ‘evil.’”

“But wait a minute,” one of the other psych grad students protested. “Everything you’ve talked about can be explained—lack of empathy, poor impulse control, the inability to imagine consequences—by scientific models. I mean, violent criminals are almost always victims of violence themselves. We don’t need the concept of evil to understand their actions.”

“Sure,” S. replied. “I use those models—I have to. That’s what I’m being trained to do. But at the same time, as a religious Christian, I also believe that some people are just evil. I can keep the two systems separate. But that’s what I feel deep in my heart.”

I was amazed and even a little appalled by S.’s admission at the time. There is definitely something disconcerting about the thought of a trained clinical psychologist who thinks that some of her patients are marked by Satan.1 But if I am honest with myself, I have to admit that I’m not 100% certain there’s no such thing as evil in the world. Now don’t get me wrong—I deeply and completely believe that violent criminals are also victims, and that if we bother to cast even a cursory glance over their life stories we will come to understand how they were shaped by violence and neglect. I deplore the death penalty, and I insist that leaving people to rot in prison is barbaric.2 But I also can’t quite shake the feeling that there is a force in the world—mostly latent, but which occasionally rears its demoniacal head—that is absolutely opposed to the principles of love, kindness, empathy, and even life itself. Sometimes it feels to me like we’re all walking around on a thin crust of quotidian normalcy stretched over a vast boiling sea of white-hot molten horror, and every once in a while—just out of sheer bad luck—some poor sap’s foot pokes through and he ends up in a basement chained to a radiator or a tiger cage being tortured with electrodes. I don’t know how else to explain the very worst atrocities of the world, and I don’t know where to put them other than a Manichean schema of good and evil.

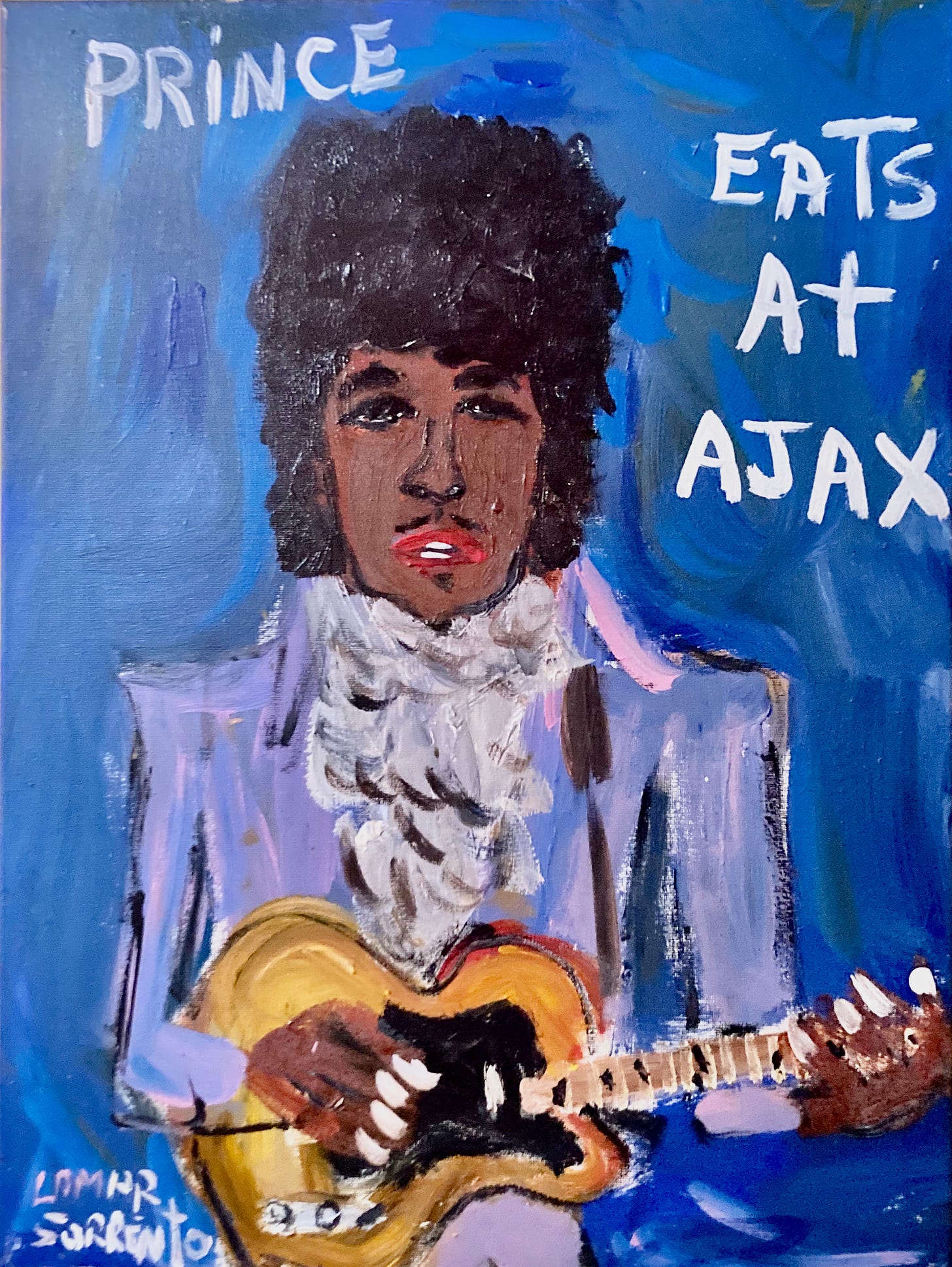

But I digress. I promise another essay on another day about the problem of evil. What I really want to talk about, the real reason I’ve been thinking about Ted Bundy and his ilk, is the upcoming anniversary of the death of Prince. No, no, no, I am not implying (horrible dictu!) that Prince was a serial killer, or evil, or a sociopath. But I do think that my fascination with him bears some disconcerting similarities to the fascination many folks have with serial killers and other outsized monstrous figures. It takes a lot of fans to turn someone into a media sensation.

In April it will be seven years since the Purple One died, and it’s been only about four or five years since I’ve stopped obsessing about it. I vividly remember the day I heard the horrible news. I was sitting on the couch in our living room, surrounded by teetering stacks of exam blue books, in the thick of a grading frenzy right after finals. I had just powered my way through a big batch of essays and recorded the grades, and was feeling pretty good about life. I opened my web browser for a quick little glance at the news, and there it was. Prince was dead and my sweet bubble of complacency was violently burst.

I barely got my grades in on time that semester. The next several weeks of my life were devoted to an obsessive deep dive into all things Prince. I could think of nothing else, read about nothing else, listen to nothing else, dream about nothing else. For the first couple of days it felt like the rest of the world was right there with me, so my behavior didn’t really seem that strange. But as the days and weeks wore on, and one by one my fellow obsessives abandoned me and returned to their own lives, I started to feel like a freak for continuing to spend hours a day reading articles about Prince’s last days and downloading bootleg versions of obscure albums I had never bothered to listen to before. I finally emerged from my rabbit hole—which, I must point out, felt very similar to a Robert Pickton rabbit hole or a Jeffrey Dahmer rabbit hole, just longer and deeper3—in time to salvage a small chunk of my summer. I think I just got tired. But to this day, I still feel a sharp little tug around my sternum whenever I see an image of Prince or hear one of his songs on a party mix. New neural pathways devoted to mourning were burned so deeply in my brain for those few months in 2016 that I will probably never have a normal relationship to that particular pop star ever again. I know I can never again set foot in Minneapolis.

Why exactly was I so obsessed? Or, another way of putting this question would be, What on earth does Prince have to do with serial killers? Here is my provisional thesis: serial killers and world-famous mega-stars fascinate us because we are forced to watch as they get away with things we know we cannot.4 It doesn’t really matter if we don’t want to do those particular things ourselves; it’s the sheer derring-do that captures our imaginations. I can’t speak for everyone, but I tend to become obsessed with these larger-than-life charismatic figures and charming narcissists out of a perverse kind of jealousy.5 Just like all women everywhere, I feel burdened by an intense social pressure always to be nice, and some unconscious imp deep inside me longs to be able to get away with being an asshole and still be admired and indulged. (You might protest that serial killers are not admired, and at least the ones we know about have all been brought to justice. And I would respond: have you taken a look at the Spotify podcast list lately?)

Let me hasten to say that I have absolutely no desire to save pieces of fellow human beings in a freezer or die alone in the elevator of my mansion. Nor do I even want to treat people badly—not consciously, anyway. I like being boring and normal and having people around me think I’m doing an okay-ish job in life and am a pretty good friend. But these dudes who treat everyone around them like garbage and still garner the fascination of young women with their entire lives ahead of them represent my shadow self, the part of me that I am trying to tamp down in order to be accepted and loved. And I suspect a lot of boring, normal people around me are struggling to do the same.

In a recent essay on our fascination with serial killers and mass murderers, the writer and podcaster Sarah Marshall proposes a slightly different thesis: “As far as I can tell, Americans love killing one another, and always have, but serial killers make us look a little better. The United States was built on the bones and blood of endless murder, of slavery, and of genocide; crucially, the FBI’s current classification of a serial killer stipulates ‘unlawful’ killings, because otherwise, a lot of cops and federal agents would be serial killers too.” I think this interpretation is pretty close to my own, but Marshall doesn’t take her conclusion quite as far. Having a convenient scapegoat to point to while protesting that “at least I’m not as bad as that” is only part of the shadow-self complex. That’s the easy part. The harder part is acknowledging that you are, in fact, just as bad as that—you’re just more completely socialized and better at repression.

I realize that it might seem like I’m resurrecting the concept of evil, just spreading it around a lot more. But I don’t think we need to think of our profound, unreconstructed desire to get away with murder as “evil,” necessarily. Psychoanalysis reminds us that these deeper drives are very much part of being human. The primary task of “His Majesty the Ego,” as Freud termed it, is to negotiate between our selfish, devilish impulses and the social strictures we must eventually internalize in order to get all the other things we want. If you prefer Netflix-and-chill with your partner and kids to a basement freezer full of body parts, this is just the bargain you make. And you made it so long ago, and repressed the making of it so thoroughly, that the bare idea that you even went through this negotiation at some point in the past outrages you to your bones.

Late at night, when I’m questioning every single one of my life choices for no apparent reason except that we have some kind of contractual obligation to do that in the middle of the night, I comfort myself by remembering that people like Prince, and Ted, and Jeffrey, and John B. McLemore were all intensely lonely and alone. There is something gloriously pure and almost magisterial about that perfect aloneness. It was our beginning and it will be our end. It calls forth in us feelings of admiration we don’t know what to do with. We carry within us ancestral memories of its clammy touch. We know that the darkness will always be there. Embracing it is the easy way out.

Apparently, belief in evil (and good) is even a field of clinical research.

“Serial killers helped us learn to see prisons as places that sealed their inhuman evil away from the rest of the world, and forget that they contain human beings.” Sarah Marshall, “Violent Delights.”

That’s what she said.

While Prince might not have been a murderer, by many accounts he treated people around him really badly, and the more he manipulated and abused his friends and employees, the more compelling he became.

My most recent obsession in this vein was John B. McLemore from the “S-Town” podcast.