Spilling the Tea: Week #3 of 52 Mini-Essays Project

On hot beverages, disappointment, and colonialism

Topic Idea: Jill Rappoport

No one seems to know the exact origin of the expression “spill the tea” (meaning to impart a piece of juicy gossip or a shocking truth), and I am now at the point in middle age where three hours spent researching it on the internet feels like three hours closer to death. It obviously comes from Black drag culture, and has been around since at least the early 90s, but its first users—praise their lacefronts—are lost to the mists of time. I like the explanation that it invokes the Southern (or British) custom of a polite social gathering around a tea service, where someone says something so surprising that it causes others to upset their teacups. Apparently the meaning has morphed over the years so that “the tea” now refers to the scuttlebutt itself.

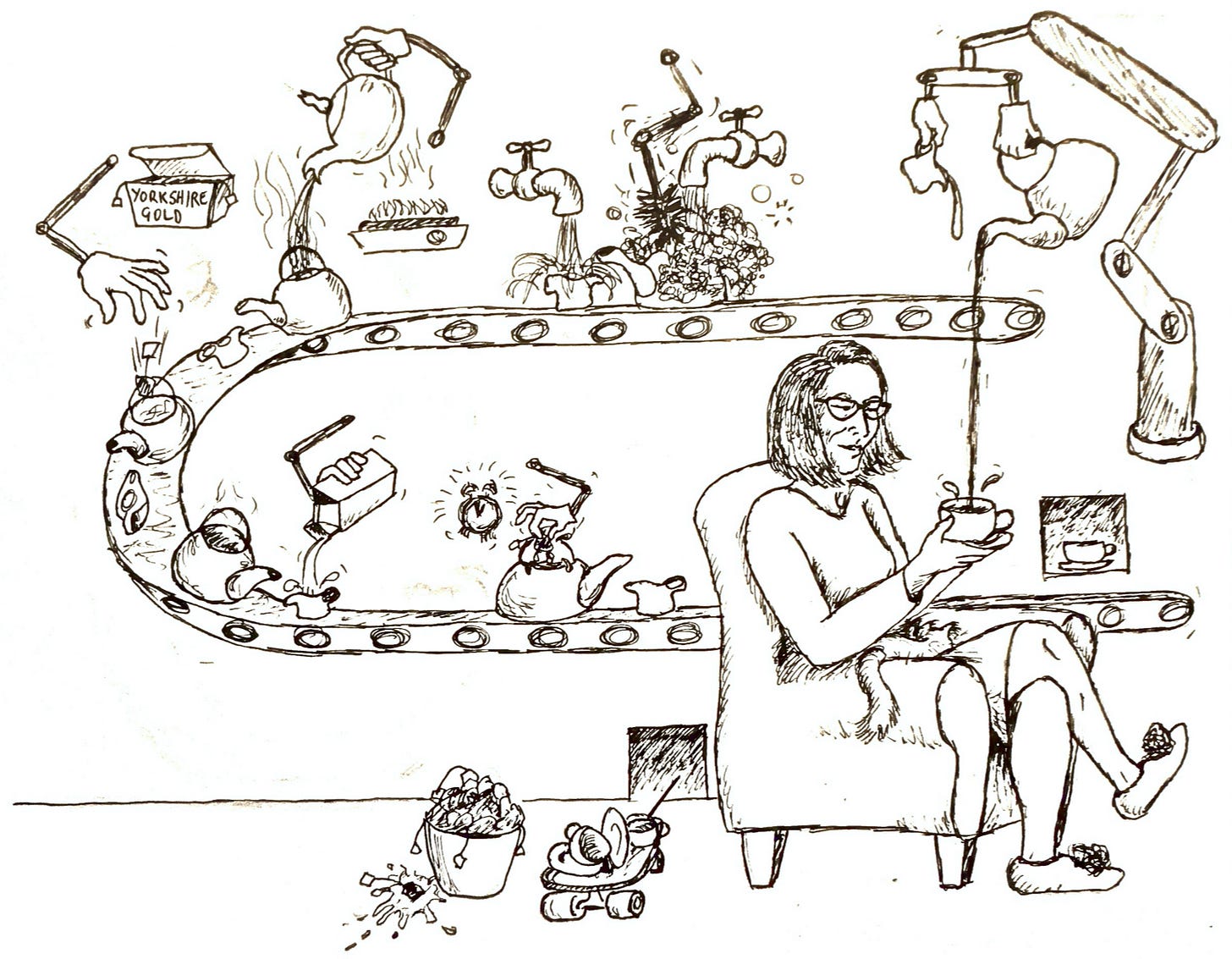

You can spill the tea about yourself or others, so “tea” doesn’t really mean gossip as much as it means valuable or interesting intelligence. Even though it’s an accidental confluence of meanings, it makes sense to me that “tea” would come to signify something valuable, because brewed hot tea is one of the Goddess’s gifts to humanity bestowed to ease our way through this vale of tears. If left to my own devices, I would drink approximately 30 cups of tea a day. I would start in the morning and just keep making cup after cup until I jumped out of my own skin from overstimulation or slipped and cracked my head open running to the toilet. If we removed caffeine and bladders from the equation, my fantasy world would feature an electric kettle on permanent boil at my elbow and a Rube Goldberg rotating-pulley machine with cups brewing, pouring, milking, warming, brewing, etc., on an endless loop. The delivery system would be timed perfectly so that just as I polished off one cup the next would be ready to drink—basically, a never-ending stream of tea entering my gullet 16 hours a day.

Because let’s get real for a second here: there is always something slightly disappointing about every cup of tea one drinks. The anticipation of the tea is always more perfect than the tea itself. Partly it’s because the idea of tea is so potent for me—and, I gather, for all 68 million inhabitants of the United Kingdom along with a buttload of Americans, Canadians, Australians, Kiwis, and other Commonwealthers. (I assume that tea drinking performs different cultural functions in Asian countries. The kind of British tea obsession I refer to has a very particular valence: comfort, communication, desperation, a sop for boredom, etc. It’s entirely likely that tea has those meanings in, say, Japan as well, but I feel I can speak only for the Anglo-American context.1) When I came home from school there was tea, in giant mugs filled with milk and sugar. I used to dream about my waiting beverage as I was walking up the street from the bus stop. It’s one of the few (if only) memories I have of my mother nurturing me. My sister and I both remember the tea, but we can’t piece together how or why or when the ritual started. My mother’s family are all from England and Scotland, but they also have been in this country since the early to mid 1600s—before tea had taken off in Europe. (Did the Puritans drink tea? Were they like Mormons? I don’t even know. But at any rate, my ancestors, Puritans all, probably were not the immediate source of my mother’s tea obsession.)

The tea that I enjoyed in my mind as I walked up Jeffrey Lane was never exactly the same as the tea I actually drank when I walked in the house. For one thing, the temperature is almost always wrong. If you make a mug or a large cup—and I mean, come on—then it will take anywhere from 15 minutes to 48 hours to finish it (the forgotten/lost/abandoned tea mug is properly the subject of its own essay), which means there is going to be a huge temperature variance from first sip to last. If you are lucky you will find one sip somewhere in the middle of the cup that is exactly right, but chances are you’ll miss it as you turn the page in your book or change the channel or answer the phone—then it’s all downhill from there, from slightly too cool to deeply disappointing to revoltingly cold. When you do manage to catch the exact-right sip in a particular serving of tea—calloo! callay!—it is unavoidably tinged with melancholy, as you know that the next sip will be ever so slightly too cool, and on from there. Of course you could try to catch the exact right moment and then immediately consume all the rest of the tea as quickly as possible, unhinging your jaw like a pie-eating-contest champ and pouring it all in at once, but then your tea would be gone.

There is no gaming this system. I have tried. I have purchased not one, not two, but three electric cup warmers to keep on my various desks (the accidentally left-on electric cup warmer is properly the subject of its own essay), but like any attempt to do an end-run around the laws of physics it was doomed to fail. It can’t really keep a full cup of tea warm, and by the time you’re at the middle of the cup the warmer is just coasting on the fact that you’re in the sweet spot anyway (trying to take all kinds of credit for stuff it doesn’t deserve), and by the time you’re in the final third or so, the heating element is scorching the tea and making it unpleasantly hot. Stop your ears against the siren song of the electric cup warmer, my friends. That way madness lies.

But there are more profound reasons that tea is bound to disappoint. A cup of tea, no matter how lovingly prepared or elegantly served,2 cannot possibly support the weight of unconscious expectation with which an inveterate tea drinker imbues it. It cannot—every mid-century British cultural product notwithstanding—actually reveal who bludgeoned the parson in the belfry or bring Johnny back from the war. It cannot replace maternal care. This disheartening knowledge does not stop the tiny little flip of anticipatory excitement I feel in my stomach3 whenever anyone utters the phrase “Cup of tea?” (The redoubtable and brilliant Victorian literature scholar Kate Thomas4 once explained to me that the British afternoon tea ritual was invented to redress the “yips,” the drop in serotonin that we experience around 4:00 p.m. every day.) My Kiwi in-laws have a whole quaint vocabulary for tea trappings—“hot drink” (which can also mean coffee or even cocoa—but I mean, come on), “jug” for electric kettle, “gumboot” for everyday black tea. The silent understanding that passes between us in these moments of tea offerings and tea acceptances is 99% of the reason I love them so much.5 My husband, technically also a New Zealander, does not drink tea. MY HUSBAND DOES NOT DRINK TEA.

Unfortunately there is no longer any way to drink tea without guilt. If you’ve been paying even a scintilla of attention to the ongoing rapine of our home planet, you now know that certain products that Westerners have come to enjoy (*cough-be-addicted-to-cough*) over the past few hundred years—cocoa, sugar, coffee, tea, dairy, beef—are so horrible for the environment that you might as well twirl your dastardly moustache and cackle with malicious glee every time you consume them.6 Some items on that list have the extra-special added bonus of being economically exploitative as well. (You know the production of a foodstuff is problematic when an entire side industry springs up dedicated to convincing guilt-ridden Global Northerners that it’s really “Fair Trade” or “Shade Grown” or “My Little Pony™ Approved.”7)

I don’t know where to put this guilt, as I don’t know where to put so many things that prop me up and give me succor and impart meaning to the void yet are actively harmful to my fellow human beings. How to disentangle what we’re responsible for, what we can address and ameliorate on a personal level, and what is structural and must await deep political change or even revolution. What to do with my appetite and desires and pleasures. How to own them as a woman in patriarchy yet disavow them as a white settler colonist. How to renounce something that ties me with the tenderest and most gossamer of threads to the memory of a remote, difficult mother.

A few months ago I researched tea grown in the U.S., and it turns out there is a company that produces environmentally and ethically grown loose tea right here in Mississippi. I ordered a bag. I did not order a second bag. (Unfortunately it tasted like virtue.) I then looked into growing my own tea in the back yard, but it turns out that the labor required to produce, harvest, and dry enough tea for a modest 2-cup-a-day habit (and I mean—come on) is roughly equivalent to that of an associate professor of English at a flagship state university. So the ethical dilemma roils on. Right now I drink Yorkshire Gold tea in bags that I order from Amazon. Not only is this practice unconscionable on every possible level, but I fear that the tea is rotting my insides. (I have a vintage tea canister I keep the bags in and noticed a little while ago that the old-timey plastic lining in the lid is pitted and corroded from—what? tea fumes?) In for a penny, in for a pound.

“Take some more tea,” the March Hare said to Alice, very earnestly.

“I’ve had nothing yet,” Alice replied in an offended tone, “so I can’t take more.”

“You mean you can’t take less,” said the Hatter: “it’s very easy to take more than nothing.”

“Nobody asked your opinion,” said Alice.

It seems important that tea came later to Westerners, stripped of the earlier ritual and cultural trappings it had in its countries of origin: it is thus a more efficient screen for projection.

From Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South (1854): “She stood by the tea-table in a light-coloured muslin gown, which had a good deal of pink about it. She looked as if she was not attending to the conversation, but solely busy with the tea-cups, among which her round ivory hands moved with pretty, noiseless, daintiness. She had a bracelet on one taper arm, which would fall down over her round wrist. Mr. Thornton watched the replacing of this troublesome ornament with far more attention than he listened to her father. It seemed as if it fascinated him to see her push it up impatiently until it tightened her soft flesh; and then to mark the loosening—the fall. He could almost have exclaimed—‘There it goes again!’ There was so little left to be done after he arrived at the preparation for tea, that he was almost sorry the obligation of eating and drinking came so soon to prevent him watching Margaret. She handed him his cup of tea with the proud air of an unwilling slave; but her eye caught the moment when he was ready for another cup; and he almost longed to ask her to do for him what he saw her compelled to do for her father, who took her little finger and thumb in his masculine hand, and made them serve as sugar-tongs. Mr. Thornton saw her beautiful eyes lifted to her father, full of light, half-laughter, and half-love, as this bit of pantomime went on between the two, unobserved as they fancied, by any.” I ASK YOU, SIRRAH, IS THERE A SEXIER SCENE IN ANY VICTORIAN NOVEL? That said, where to begin unpacking the issues in this passage? With the metaphor of slavery, the expectation that the function of woman is to have another cup ready for man as soon as his previous one is empty (at least I imagine a machine doing this for me), with the sexualization of the heroine’s obvious frustration and physical discomfort, with the fact that I still find this scene really hot regardless/(because of???) all of the above?

Modern neuroscience would tell us this is a hit of dopamine.

She also writes brilliant scholarship about tea! “A Cup of Tea and a Sit-Down: Sensation, Fiction and the Imperial Sensorium,” currently under review.

Totally kidding! I adore them all because they are wonderful and amazing. If they stopped drinking/offering me tea, I’m nearly 100% certain I would still love them just as much.

Don’t be mad at me! You know it’s true. That said, I have not been able to give up any of these delicious items myself (although I am trying to cut back drastically on all of them), so no judgment from me. I fear that it would be nearly impossible to ask people to give up, in particular, coffee, sugar, and chocolate. For one thing, there is an entire feminist cartoon-strip industry wholly dependent on these products.

Of course all the listed items—and so many more more!—are produced by industries that wring the life out of their workers as well as the environment, but coffee, tea, cocoa, and sugar also come primarily (or only) from impoverished post-colonial nations. And by an extraordinary coincidence, they are all products whose global demand was inaugurated by colonialism and inculcated by slavery. Who would have guessed!