Sock It to Me: Week #18 of 52 Mini-Essays Project

On covering your feet and covering your bases

Topic Idea: Jill Rappoport, with an assist from Sandy Huss

“Socks are the worst and should be abolished for all time.” I promised my friend Sandy H. that this would be the first line of any essay I wrote on the topic of socks. I had been a bit worried that the subject was too trivial, perhaps unworthy of sustained attention. Who would want to read an essay, however mini, on such a picayune topic? Who did I think I was, Nicholson Baker nattering on about fingernail clippers? Apparently I need not have worried, since (as we shall see) Sandy is not alone: it turns out that the mere idea of covering one’s feet in soft, knitted material is capable of rousing the deepest passions in the human breast. Now that I have fulfilled my solemn oath to my friend and begun my essay with her exhortation, we can move on to the deeply important business of considering socks in all their sockiness. What do we actually mean by the word itself? What does it take to be a sock? Do we indeed hate them, and if so why? Who is responsible for bringing the sock to humankind, and were their intentions benevolent? Whence, whither, wherefore socks?

Let’s start with some definitions. (Before I turn to the OED, I would like everyone to take a moment to appreciate the fact that I have come this far in the 52 Mini-Essays Project—well into the double digits!—before beginning an essay with a dictionary definition. I mean, it was inevitable that I eventually fall back on this hackneyed device, but I want some props for putting it off for so long.) According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first non-obsolete meaning of “sock” is: “A short stocking covering the foot and usually reaching to the calf of the leg; half-hose.” Now this is patent nonsense. I would venture to guess that the majority of socks these days fail to reach the empyrean heights of even the mid-calf—let alone covering the entire tibio/fibular area. (This is particularly true, of course, of sport socks and women’s socks.) But even if the majority of half-hose do indeed reach nearly to the knee, a significant proportion of socks do not aspire to the calf at all; it is thus gross irresponsibility on the part of the OED lexicographers to build this criterion into their definition.1

This was not an auspicious start. On the off chance that the problem was due to the stuffy, hidebound (*cough*British*cough*) nature of that particular tome, I next consulted the New Oxford American Dictionary (Third Edition) which I just happen to have in hard copy right here on my desk.2 According to the folks who compiled this freewheeling lexicon (on my way to “sock” I passed a definition for “space blanket” and a sketch of Harrison Ford), the primary definition is “a garment for the foot and lower part of the leg, typically knitted from wool, cotton, or nylon.” This is even worse. Whereas the OED had left ambiguous the question of how much territory a sock must cover in order achieve sockhood (the phrase “reaching to the leg” [emphasis added] could surely support a rich, multifarious exegesis), the Americans seem to have doubled down on the calf requirement. The blithe assurance that all socks worthy of the name must cover at least part (if not all!) of the lower part of the leg is, frankly, the worst kind of national hubris. We know best; our way is the only way; we are unable to imagine a world in which socks cover only the foot or stretch all the way up to the crotch: absolutely typical of my compatriots. No wonder people are mean to us in Paris.

It’s becoming clear that we need to move beyond mere dictionary definitions if we want to get closer to the deep nature of sockhood. (By the way, I will be starting a letter-writing campaign to the editors of both dictionaries encouraging them to update their definitions, so watch this space.) Perhaps a historical survey would be more illuminating. A quick Google search3 for “history of socks” reveals that many, many unemployed lunatics have considered this question long before me. From “Sock History” and “The History of Socks” to the slightly racier offerings “When Were Socks Invented” and “How did socks come into existence?” (that last one clearly written by a stoned ex-philosophy major), the internet has us—if not our calves—covered. You will be relieved to learn that as part of the public service mission of the 52 Mini-Essays Project, I have read through these compendia and will summarize for you what I have learned.

Our earliest evidence of sock-like objects in use by the human species comes from cave paintings and archaeological finds: around 5000 BC, some enterprising souls began wrapping animal skins around their feet and then tying the skins around their ankles. This research and development team was clearly annoyed at being pulled off the much more glamorous Harness Fire and Invent the Wheel projects, and decided to half-ass it in protest. I mean—animal pelts? Hot, stiff, uncomfortable, non-absorbent—you might as well dip your feet in molten tar and let it harden into a permanent carapace. Weren’t there any nice cool flexible leaves lying around? This just seems like a perfect example of the stereotypical Paleo mindset: use animal products for everything. I guess if you’re planning to die by age 25 it doesn’t matter how much cholesterol you ingest or how disgustingly sweaty your feet are.

By the 8th century BC, Hesiod is mentioning “piloi” in his long didactic poem Works and Days: this is a kind of sock made from matted animal fur (I can’t even) and worn under sandals. There is no excuse for this sartorial choice; I don’t care if you are an ancient Greek agriculturalist or a German tourist relaxing poolside in Vegas. If you are wearing sandals you should not be wearing socks, and vice-versa. End of discussion.4 Unfortunately, this message took quite a while to get through. The oldest surviving knitted socks (now we’re getting somewhere) date from around 400 AD and were discovered on the Nile River in Egypt. Unfortunately, they featured split toes and were designed to be worn ... with sandals. Frankly, humankind is being very dumb about this socks business. It doesn’t seem like it took this long to figure out, say, tunics.

The first woollen socks actually appear a bit earlier in the archaeological record: a child-sized pair, dating from around 200 AD, discovered at an ancient Roman site in Northumbria. Apparently the Roman occupiers devised a rough woollen cloth to protect themselves from the British weather—that harsh maternal necessity to so many inventions—which they took to wrapping around their feet. Tablets discovered at the site include the instructions “send more socks.” This detail simply kills me. A plaintive call across the centuries from a sad-sack bureaucrat moldering away at some god-forsaken outpost, the missive didn’t even make it to its destination. Did he entrust it to a rakish courier who stopped off for a quick one at a local taverna, was distracted by the limpid gaze of the barkeeper, and accidentally dropped it behind a cistern where it lay for the next 1800 years? Whatever happened to the heartfelt plea, one thing is clear: its sender died in anticipation, bereft, and with unnecessarily cold feet.

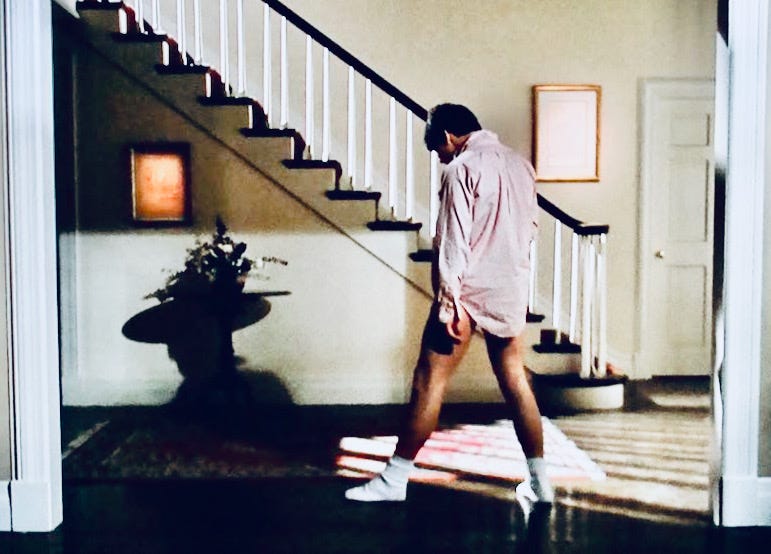

Skipping ahead a bunch of centuries in our very bumpy sock development story: during the early Middle Ages, breeches became longer and men began to wear tight, brightly-colored cloth around the lower part of their legs. (Because.) Since there was no such thing as elastic yet, these fancy dudes wore garters over the top of their stockings to prevent them from falling down, a horrifying state of affairs that will continue until well into the 20th century. Fun weird fact: these earliest socks had no feet. (Talk about pushing the very boundaries of the definition! I hereby protest that these medieval vanity objects are actually leg-warmers, and should be acknowledged as such. Get your own damn history and fluffy mini-essay, leg-warmers! You can have Jennifer Beals. We get Tom Cruise.5) It wasn’t until the 12th century that feet were added to leggings, or whatever the hell they were called, to produce what we now think of as socks. These new garments are not actually called “socks,” however, until the 17th century. The English word sock comes from the Old English socc, meaning a light slipper, which is derived from Latin soccus, a low-heeled shoe worn by Roman comic actors, which in turn comes from the Ancient Greek word sykchos.

But we are getting a little ahead of ourselves, since I would hate to skip over the single greatest period in the entire history of sock development. Because in the Renaissance silk socks were a status symbol that only the wealthy could afford, they came under the purview of sumptuary laws regulating what articles of clothing, fabrics, and even dye colors the various classes were allowed to wear.6 Elizabethan lawmakers felt very, very, very strongly about socks: “And for the reformation of the use of the monstrous and outrageous greatness of hose, crept alate into the realm to the great slander thereof ... : it is ordained as abovesaid that no tailor, hosier, or other person, whosoever he shall be, after the day of the publication hereof, shall put any more cloth in any one pair of hose for the outside than one yard and a half”—and on and on it goes, a clearly desperate and doomed attempt to govern the ungovernable. Apparently, by the late 16th century the City of London was employing actual sock police, four “sad and discreet” persons who were positioned twice a day at the gates of the city, checking the legs of those coming and going to make sure that no one was wearing hose inappropriate to his station.7

The next big revolution in sock production came with the invention of nylon in 1938 and of elastane in 1958, at which point humankind was freed forever from the onerous garter. (You can still buy them, though. Why?) And that brings us up to the modern sock situation of today, when as a society we enjoy a wide range of sock shapes, styles, lengths, and modalities. A tiny slip of elasticized cotton covering only your toes and the back of your heel, designed to be invisible under sneakers, is no less a sock (pace the Oxford lexicography team) than a banded Argyle knee-high worn with a Scottish kilt. And I will die on that hill.

Several things have become clear through our brief historical survey. First of all, our species has always found it very important to cover our feet, and even more important to buffer them from shoes. This makes perfect sense when you consider the practicalities involved: socks add warmth, blister protection, and sweat absorption (which is why—again, not to beat a dead horse, but I think it bears repeating—no one needs to wear socks with sandals). Second of all, and somewhat paradoxically, humankind struggled for an inordinately long time to figure out the sock thing. Granted, we had to wait for the invention of advanced synthetic polymers to really perfect the design, but it still seems as though it took much longer to figure out the basics than one would have expected. (Animal pelts tied around the ankle? Please. You’re just embarrassing yourselves.) It seems unlikely that there was this much fussing over mitten or hat design, objects that are also crucial to human comfort and protection. And finally, people seem to have had extraordinarily strong feelings about socks, both positive and negative, from the beleaguered Roman functionary to prissy Queen Elizabeth straight through to my friend Sandy. Again, it’s hard to imagine any other accessories fomenting this much passion. I don’t know anyone who gets this exercised over the very existence of scarves, say, or watch bands.

Rejecting the sock, hating it, is a privilege of advanced civilization. We can afford to eschew socks now that we have central heating and spend much of our lives indoors, communicating with others through our computers, instead of pulling turnips for a living. Now we signal our cultivation not through ever longer, silkier, more voluminous hose, but rather through abandoning foot coverings altogether. It’s impossible to imagine medieval peasants or even Tudor nobles padding around their drafty domiciles barefoot. We have arrived at a state of modern comfort and convenience that enables us to let our feet hang out, unencumbered, 24 hours a day and 365 days a year if we so desire. Is there a more trenchant symbol of fossil-fuel modernity, of life in the global North after the Great Acceleration, than this?

I personally do not hate socks, but I am not a super-consumer, either. People tend to give me socks as gifts, usually literary-themed, which I find utterly delightful. (In just the past couple of years different friends have given me a pair of Jane Austen socks and a pair of Charlotte Brontë socks. Neither of these authors would recognize the objects on which her likeness is stitched, but I’m not going to lose any sleep over it.) I tend to wear slippers around the house—and I hope we’ve come far enough together on this sock-discovery journey that I don’t have to explain that you should not be wearing socks with slippers. Perhaps that is the subject of another essay.

For a long time, in my 20s and 30s, I struggled to find my own perfect sock length. Even though I will fight to the death to defend the right of anklets to be considered socks, I must admit that I like to have part of my own calf covered by fabric. Not all the way to the knee—god no. Unless you are a cheerleader, a field hockey player, or a bagpiper, there is no excuse for the knee sock. But I think it feels cozy to have at least part of the calf swaddled, which makes it a real problem to find comfortable socks. In order to defy gravity for any length of time, a mid-calf sock has to have extremely powerful elastic, which means that by the end of the day you have painful red welts circumscribing your lower legs—not to mention the fact that the elasticity eventually gives out and your socks start bunching around your ankles. And this is actually where I’ve landed. I’ve learned to embrace the deliberately slouchy sock, the sock that can’t be bothered stretching beyond its proper place and then clinging desperately to hang on. The sock that is okay with not being as taut and firm as it once was. The accidental ankle sock. The modest sock, the friendly sock, the sock that just wants to do a pretty good job and call it a day. The sock that knows itself. The sock that has learned how to let go.

They do refer the reader to a separate category of “ankle socks,” but by siloing them off into their own entry (you have to turn to another page/click on another link!), the dictionarios have implied that the category of “real” socks does not comprise anklets.

I am serious.

Please note that I am now turning to the second-hoariest essay-opening cliché, but once again I am waggishly drawing your attention to that fact which makes it all okay.

Oh, all right: here is another opinion (*shudder*).

Come to think of it, this is a terrible deal.

For the crazy people: “And for the reformation of the use of the monstrous and outrageous greatness of hose, crept alate into the realm to the great slander thereof, and the undoing of a number using the same, being driven for the maintenance thereof to seek unlawful ways as by their own confession have brought them to destruction: it is ordained as abovesaid that no tailor, hosier, or other person, whosoever he shall be, after the day of the publication hereof, shall put any more cloth in any one pair of hose for the outside than one yard and a half, or at the most one yard and three-quarters of a yard of kersey or of any kind of cloth, leather, or any other kind of stuff above the quantity; and in the same hose to be put only one kind of lining besides linen cloth next to the leg if any shall be so disposed; the said lining not to lie loose or bolstered, but to lie just unto their legs, as in some ancient time was accustomed; sarcanet, muckender, or any other like thing used to be worn, and to be plucked out for the furniture of the hose, not to be taken in the name of the said lining. Neither any man under the degree of a baron to wear within his hose any velvet, satin, or other stuff above the estimation or sarcanet or taffeta.For the due and better execution and observation whereof, the Mayor of London and the rulers and officers of the suburbs and of Westminster, and other exempted places, shall immediately, after this proclamation made, call before them in every of their several jurisdictions all hosiers or tailors making hose dwelling within the precincts of the same, and shall bind every of them in the sum of £40 or more as cause shall require, to the Queen's Highness's use, to observe this part of this said proclamation touching hose, without any manner fraud or guile; which bonds, as any shall be found to offend contrary to this ordinance, they shall certify into the Exchequer with the name of every such offender. In all other cities or towns corporate the mayor and head officers shall do in all points the like, and in all other places the justices of peace; the officers of the Exchequer to certify the Lords of the Queen's Highness's Privy Council at the beginning of every term what bonds have come or have been sent into that office touching the premises till that day, and what number of them have been executed.If any hosier shall refuse to enter into such bond, to be immediately committed to ward and to be suffered no more to continue his occupation.Finally, no men undispensed with, in such sort as is abovesaid, be so hardy after 14 days following the publication of this ordinance, to presume to show himself in the Court, or in any other place within this realm, in any pair of hose passing the size abovesaid; that is to say, containing in the netherstocks and upperstocks more than one yard and a half, or above one yard and three-quarters at the most, of the broadest kersey, or with any other stuff beyond that proportion, or with more linings than one and that plain and just to the legs as is abovesaid; ... upon pain of forfeiture of the same and of imprisonment and fine at the Queen's Highness's pleasure for every such offense, to be executed within the Court by such as shall be appointed, in sort as is aforesaid, by the Lord Chamberlain, Vice-Chamberlain, the Lord Steward, the Treasurer, and Comptroller. And in London and within the liberties thereof, to be executed by the sergeants and such others as shall be appointed in form aforesaid, by the mayor and aldermen. In the suburbs, Westminster, and other privileged places, by the officers, rulers, and governors of them; in all other places, by the head officers and justices of peace.... Her Majesty straightly chargeth as well the said Lord Chamberlain, Vice-Chamberlain, the Lord Steward, the Treasurer, and Comptroller of the household, as the Lord Chamberlain, Vice-Chamberlain, and such as under them shall be appointed and assigned, the Mayor of London, and all other mayors, sheriffs, bailiffs, constables, and justices of peace, all principals and ancients of the Inns of Court and Chancery, the chancellor and vice-chancellor of both universities, and the heads of halls and colleges of the same, and all other her Highness's officers and ministers, each of them in their jurisdictions, to see these orders being set forth and confirmed by her Majesty's proclamation, to be duly and speedily executed in form aforesaid, as they will answer for the contrary at their peril, and will avoid her Highness's displeasure and indignation.” [Westminster, 6 May 1562, 4 Elizabeth I]Printed by R. Jugge and J. Cawood (London, 1562): Articles for the execution of the Statutes of Apparel, and for the reformation of the outrageous excess thereof grown of late time within the realm, devised upon the Queen's Majesty's commandment, by advice of her Council, 6 May 1562

Queen Elizabeth I had a whole bunch of issues with socks. In 1589, an English clergyman named William Lee invented the first circular knitting machine for the production of hose. (Its basic design is still in use today.) The patent was not immediately granted, however, since his monarch found knitted stockings uncomfortable. King Henry IV of France was able to see the opportunity the new machine presented, and invited Lee to move to France and mass produce stockings—wool for the working classes and silk for noblemen.