Dead Letters: Week #37 of 52 Mini-Essays Project

On epistolary second-guessing and things that go astray

This essay is kind of a prequel to this one, and therefore the topic idea is indirectly thanks to Tobias Wilson-Bates

I am of two minds about the whole cleaning-out-the-dead-person’s-house situation. On the one hand, it’s a ritual that can bring real comfort to the grieving relatives and friends charged with the task. The hours, days, weeks (okay, months) spent going through the closets, attics, basements, garages, sideboards, cedar chests, liquor cabinets, and cutlery drawers of the deceased, sorting their worldly chattel into Keep, Throw Away, Goodwill, and ??? piles, is as close as many people get to a religious ceremony. Now that most Americans no longer wash and wrap the bodies of our dead and pray over them by candlelight, the closest we get to a final goodbye to their physical form is fingering all their earthly belongings. There is real solace, and even pleasure, to be had in pawing through secret stashes of stuff you never had access to as a kid, re-encountering forgotten childhood objects, laughing and reminiscing with your fellow toilers in the household midden.

On the other hand, just set the house on fire and be done with it.

When we were clearing out my parents’ place, my partner Scott was particularly tickled by what came to be known as The Incident of the Vault. We survivors and heirs—my sister, niece, Scott, and I—were surprised to discover that my parents had kept a small fireproof safe in the garage attic. No one knew the combination, so our imaginations ran a little wild for a few days before we could get it open. My dad’s OCD tendencies had, in the last few years of his life, shaded over into light hoarding flavored with a soupçon of survivalism. There had been a lot of dark mutterings about banking collapses and Krugerrands, so we all secretly hoped we were about to discover a stash of gold bullion, just like in a nineteenth-century novel.1 When we eventually found the combination scribbled on a slip of paper in my father’s desk we all rushed to the garage and crowded around while my sister opened the safe. Inside were all of Dad’s income tax returns dating back to 1964 and my sister’s and my elementary school report cards.2 My daughter, O my ducats, O my daughter!

My sister’s and my favorite house-clearing moment, on the other hand, was when we unearthed The Cavalcade of Colognes.

As therapeutic as this whole house-clearing process may be, however, I have to say that letters really fuck everything up. If your deceased person was of a certain age and of a certain mien, they likely will have saved actual paper letters and cards they received over the years. By their very existence, such items pose an ethical dilemma. Do you read them? If so (or if not), what do you do with them then? Preserve them, throw them away, burn them in a dramatic bonfire? If you’re very lucky, your deceased person is famous enough to warrant donating their correspondence to an archive or the Library of Congress—but as Jerry Seinfeld famously says to George Costanza when the latter fantasizes about becoming the manager of a baseball team, “That can be tough to get.” It feels monstrous to destroy them, but equally weird to lug them back to your own attic, where they will wait to be rediscovered by the people going through all your stuff after you die. I guess if you engage in such intergenerational letter-lugging long enough, eventually they will become important to collectors and archivists through sheer antiquity, regardless of whether your person was at all famous or interesting. I’m pretty sure that Samuel Pepys, the famous 17th-century English diarist, was just some random guy.

As weird and eerie and discomfiting as it can be to come across troves of your loved one’s letters, that weirdness and eeriness and discomfiture are multiplied a hundredfold when the letters are ones you yourself sent. Encountering an envelope addressed by your own hand, with molecules of your own saliva trapped under the flap and the postage stamp, the folds of the letter within created years before by your own thumb and forefinger—the intimacy is almost grotesque. Potential mortifications abound. First there’s the chagrin of learning that your dead person saved your letters at all. Discovering hard evidence of your importance to them is gratifying, true, but a slightly ickier emotion might linger after that initial flashbulb pop of self-importance. I’m sure someone (the Germans, the Japanese) has coined a term for the slight feeling of pride mixed with a slight feeling of condescension you feel for someone who is more into you than you’re into them. Discovering that your loved one has treasured up your correspondence (especially if—oh ick!—you have not saved theirs) is just like learning that the club you’d been clamoring to join has accepted you as a member after all. What a letdown.

In other words, letters are supposed to decently withdraw after they’ve done their work, like a royal servant backing away from the sovereign. And yet they’re not supposed to disappear too soon, either. I’ve always been intrigued by so-called “dead letters”: undeliverable mail that ends up sloshing around the postal system, sometimes for years. In the United States, all such correspondence ends up at a central office in Atlanta, where it is opened to determine if there are any clues to where it can be sent; if there aren’t any, it’s destroyed to protect the privacy of the sender and sendee. Or at least that’s what’s supposed to happen. Sometimes dead letters go astray, are snagged by collectors or philatelists and end up being sold for big sums, or rarely (*shiver*) they end up being delivered after all, years or decades after they were sent. News stories about such letters pop up periodically. One recent one involved a card that was sent by a solider to his mother at the end of World War II that was delivered 76 years later: “Dear Mom. Received another letter from you today and was happy to hear that everything is okay. As for myself, I’m fine and getting along okay. But as far as the food it’s pretty lousy most of the time. Love and kisses, Your son Johnny. I’ll be seeing you soon, I hope.” Talk about disappointing posterity!

The dead letter that doesn’t end up properly buried by the post office but is revivified by accident—I guess we could call it a “zombie letter”—is a pretty good plot device. One of the first detective novels written in English, The Dead Letter by Seeley Regester (1866) is narrated by an employee of the dead letter office in Washington D.C., who comes across a “time-stained” envelope that exudes a strange “magnetism,” a “strongly-defined, irresistible influence” that forces him to illicitly read it and thereby get sucked into a mysterious murder case. Since then there have been numerous novels, movies, TV shows, and even LPs that have hinged on the device of the long-lost letter that reappears unexpectedly. Maybe one of the reasons the zombie letter is so fascinating, so deliciously creepy, is that it’s a letter that has gone astray twice: first it failed to reach its proper destination, then it was supposed to be destroyed but wasn’t. We all love a good underdog story. The zombie letter is like an epistolary comeback kid.

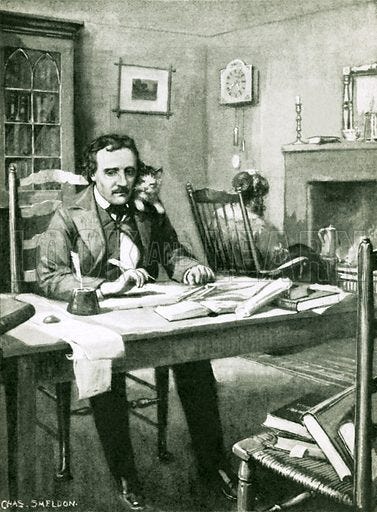

The single greatest literary use of a misdirected/lost/stolen/revivified piece of correspondence is, without question, “The Purloined Letter” by Edgar Allan Poe. If you have not read this delicious and perfect short story, then by all means set aside these natterings and go read that instead. I’ll avoid spoilers here, but the basic plot is thus: an incriminating letter from a European queen to her lover is stolen by a blackmailer, affairs of state are at stake, a dunderheaded policeman is engaged, he dunders, then finally the brilliant armchair detective Auguste Dupin cracks the case by being a scintilla more brilliant than the brilliant blackmailer. Oh, okay, never mind, I can’t stop myself: I am going to spoil the story. Look away! (Or go read it first.) The delicious and perfect hook is that the brilliant blackmailer has hidden the stolen letter in plain sight, by disguising it as a worthless visiting card and placing it nonchalantly on his mantelpiece alongside a bunch of other grubby items. Night after night the dundering policemen search his apartments with probes and awls and rulers, microscopically examining every possible hiding nook, while overlooking the letter sitting right out in the open. Dupin notices it immediately during a trumped-up visit to the blackmailer and toys with him (and his client, and us) for a while before revealing the truth.

As Jacques Lacan notes in his famous Seminar on “The Purloined Letter,” the structure of the story is quite odd, as there is properly speaking no suspense—Dupin solves the mystery immediately—and Poe has to spin things out by organizing the narration so as to delay the revelation of the truth. But Lacan also points out that the story hinges on an occult property of correspondence itself: “For a purloined letter to exist, we may ask, to whom does a letter belong? ... Might a letter on which the sender retains certain rights then not quite belong to the person to whom it is addressed? Or might it be that the latter was never the real receiver?” This is a query we can make about all correspondence, and it’s the reason that the question of the ownership of sent letters is so vexed.3 An honorable person returns, or at least offers to return, an ex-lover’s letters upon the end of a relationship; there are many reasons why the ex might not want his or her tender lucubrations to remain in the hands of the enemy. (The modern version of this conundrum is the voluntarily proffered and received nude selfie. Suffice to say that as a culture we have most definitely become less honorable, as well as less literate.)

The second-best lost literary letter is the heartbreaking note that Tess writes to her asshole fiancé in Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles, in which she confesses her unfortunate past and begs his forgiveness.4 She slips it under his door a few days before their wedding, but it slides under the carpet on the other side so he never sees it. This misplaced missive is a bit of an odd duck, though, since it’s neither a dead letter nor a zombie letter according to our strict definition. A few days after sliding the letter under the asshole’s door, Tess goes up to his room to see if he’s read it, where she finds the “faint white margin” (SYMBOLISM ALERT) of the envelope sticking out from under the carpet. She lacks the will to go through with her confession after this near-miss, so destroys the letter. A series of preventable tragedies ensues.

Rarely do we get the chance to un-send a letter we’ve sent, to think twice about what we’ve said days (or decades) later and decide whether we still want to say it. (Now that we send almost all our correspondence electronically, our opportunities for re-thinking are even more curtailed. I’ve set up a ten-second delay on my email program, but that’s hardly long enough for a serious re-think about that blisteringly angry reply you’ve just pounded out; it’s meant more as a little buffer where you can quickly undo that “Reply All” message you just sent to the whole listserv.) And this is the real reason that finding your correspondence in a dead loved one’s possession is unnerving. Here is your chance to revisit what you said long ago, and to decide whether you would still want to say it. That is exactly what happened to me when I was cleaning out my father’s desk.

My relationship with my dad was complex to say the least, and I spent years courting his attention and then feeling slightly grossed out when he acted too needy. It was like Harry Chapin’s “Cats in the Cradle,” except instead of a dramatic late-life comeuppance where the father realizes he has no relationship with his grown son and regrets having neglected him for years, my father and I played out this fort-da drama throughout my childhood. One weekend I would beg him to take me to a Phillies game but he was too busy with work or golf; the next he would pester me to accompany him on a “date” to the hardware store but I wanted to stay home with my Nancy Drews. When he was waiting to die from metastasized melanoma but was still compos mentis, he used to talk with great bitterness about how his life had amounted to nothing, lamenting that he had failed at the only thing he’d considered important—making money—and complaining that his final days were reduced to tending my mother, who had severe dementia, and hoping she would die before he did.5

I spent a lot of time agonizing about the horrible lack of meaning in my father’s life. I felt somehow responsible for his emptiness and superficiality, his obsession with material markers of success, even though there was no reasonable interpretation in which his shallowness was my fault. I suppose it was a species of survivor guilt: I considered myself lucky to have stumbled across Sartre and Buddhism and poetry at a tender age, and thus felt like I’d been grappling with the Big Questions most of my life. (Nota bene: I do not think this predilection necessarily makes my life better or more meaningful. One of the possible side effects of grappling with the Big Questions for so long is that you eventually work your way back around to appreciating unmediated experience and wishing you weren’t so fucking self-conscious about everything.) I also had been in therapy since my early twenties, so was really good at navel-gazing.

My shrink suggested that I write a letter expressing my appreciation for my father. She cautioned me against expecting any kind of satisfying response, as well as against more subtle and insidious expectations: that I might save his soul, or expiate my own guilt. (Did I listen? Of course not. That is why therapy is never over.) In the end I sent my dad a long heartfelt letter in which I thanked him for many specific ways in which he’d supported and nurtured me as a father, and also listed all the things I admired about him:

You always face a problem or a challenge with a detailed plan of attack, usually involving yellow legal pads. Even if you’re initially daunted by a new dilemma, you never allow it to defeat or depress you: you read about it voraciously, you think about how to confront it, you identify what resources you need to face it, and you figure out how to move forward. While I don’t think you ever explicitly taught me this skill when I was growing up, you didn’t have to; I saw it modeled for me every day until it was deeply internalized as a good method of living....

But you don’t practice this method just in times of crisis; it’s also the way you approach leisure and pleasure, as well. When you become intrigued by a new activity or hobby, you throw yourself into it with wholehearted enthusiasm, curiosity, and a desire to learn. I’m sure I’m forgetting some key activities here, but in the time since I was born you’ve been a pilot, a tennis player, a golfer, a sailor, a painter, a landscape designer, a chef, and a wine enthusiast. It’s been incredibly fun over the years to witness your enthusiasm and happiness in these activities, and to benefit from them as well. I hope that you continue to get satisfaction from your hobbies and pursuits—either these, or even new ones—for a long time to come.

Was I trying to give my father a retrospective sense of meaning for his own life? You bet your sweet ass I was. Is it a good idea to try to do something like this for another person? I don’t really know.

My dad did respond, in a short email which read, in its entirety:

One word. Flabbergasted.

But thank you so much. I wanted to cry.

Love,

Dad

“I wanted to cry.” “Well, why didn’t you?” I could have responded—but didn’t. There’s not really any point in trying to get a man in his 80s to rejigger his emotional mechanism so that it can produce tears. I understood what he meant, and—as always—it would have to be enough.

When we cleared out my father’s desk after his death, I came across a large manila envelope with a print-out of my letter inside, along with a bunch of official school pictures of me from various ages. They were different sizes—some were the little wallet-sized ones, and a couple were the full-sized portraits that had never been framed. I assume that when he received my letter, my father started racking his memory for the emotional connections I had described, and maybe used the photos as a kind of aide-memoire. It’s unsettling and touching and icky and gratifying and hilarious and sad—help us out here, The Germans or The Japanese—to think of him sitting at his desk, staring at a photo of me with badly cut bangs, a lumpy sweater, and no front teeth, trying to dredge up some long-lost feeling of tenderness for his middle-aged daughter. I guess it says something about me that I go straight for the most depressing and cynical interpretation. But I guess it says something about him, too.

Even at the time I sent it, I felt this letter was somewhat disingenuous. It described only the good things about my relationship with my dad—nothing about the beatings or alcoholic rages—and I had to struggle a bit to come up with the happy memories I described to him. But I don’t think that makes it fundamentally untrue; maybe it just makes it a mercy. My dad grew up dirt-poor with an abusive father on a dairy farm in the 1940s, and his whole life was an extended labor to prove his manhood, his entire selfhood, by making a good living and providing for his family. I couldn’t bear to let him leave us thinking he’d been a failure. Even though, by any metric that mattered to me personally—self-awareness, capacity for intimacy, intellectual accomplishment, spiritual growth—he was. So I guess the letter was, on some level, a white lie.

I have an old friend, R., who’s a retired emergency room nurse as well as an unreconstructed hippie. He was imprisoned for draft-dodging during the Vietnam War, and when he was inside he opted to train as a nurse in exchange for early release. I don’t think he planned to enter one of the most emotionally difficult specialties in nursing, but he ended up in the ER because of a kind of natural gift: he was very good at helping people die who had woken up that morning with their whole lives ahead of them. Sometimes he had only a minute or two with a critically injured person, who was often terrified, confused, in pain, and alone. He was the last person they saw on this earth, and he had a knack for helping them find a moment of peace before they let go. I guess this is something like what I was trying to do for my father.

Is it better to die with a softened version of the truth in your head, with a bit of Vaseline rubbed around the lens you train on the past? Or is a deathbed the time to get it all out, let loose the repressed secrets and unvarnished emotions you’ve been stuffing down for years? I guess it depends on what you think death means: a final goodbye, a temporary parting, a time of judgment. But if letters are anything to go by, the dead are never truly dead. Maybe it’s best to be on good terms with them, at least for a while.

One of the family seemed to remember Dad doing a lot of strange unexplained digging in the garden in the months before he died, which fueled all kinds of wild speculation among us heirs. The closest we came to finding a windfall among his ephemera was an envelope with ten 100-dollar bills in it that I nearly threw in the trash. To this day, though, I’m not 100% sure that there isn’t a mound of gold still buried somewhere in my parents’ former back yard.

Apparently I was “one of those who got a perfect score over all the reading sections of the achievement test” and “also did well in math.” And there is the story of women and STEM for the past 500 years.

Or at least ethically vexed. The legal question is pretty straightforward: the writer of a letter retains copyright of its contents, and the recipient may not reproduce or publish it without permission. The actual physical letter, however, is the property of the recipient, who may keep, discard—or sell—it at will. The estate of Jacques Derrida, the (in)famous doyen of deconstruction who was fond of using the “dead letter” metaphor in his philosophical writings, was fittingly/paradoxically embroiled in a lawsuit over the ownership of his correspondence after he died. Which would be kind of like the heirs to the Kentucky Fried Chicken fortune battering and frying Colonel Sanders after his death.

Of course the real tragedy is that she feels the need to ask forgiveness for having been sexually assaulted and impregnated. Hardy is actually pretty cool on this question, regardless of his inability to imagine a fulfilling life for his “fallen” heroine.

Spoiler alert: she did not. My father’s biggest worry came true: when he went into hospice my sister and I had to put my mom in a nursing home, where she lived another year in circumstances every bit as grim as he had feared.

Thank you as always. I also reread the “prequel” (important and lovely all over again), am seized by the urge to throw out much of my correspondence (even thank-you cards from students?) but save my diaries, and have to say I am really glad you wrote that letter to your dad, white lies and all, and that he responded as he did. I understand completely why you are of two minds about both, and perhaps I am too much at a distance, but what comes across from your post seems so positive all around.